Simulation-based education is now an established and curricula-integrated pedagogical activity in health professions education with the debriefing component seen to be critical to learning. There is limited empirical research examining the debrief activity, specifically addressing the question of how are interactions in simulation debriefing related to participant learning? The research that does exist is disparate, with researchers selecting different foci of interest, thus producing siloed knowledge. There is a need to both synthesise the current literature whilst simultaneously furthering the subject knowledge.

This is a protocol to undertake a systematic meta-ethnography in accordance with Noblit and Hare’s established methodology, consisting of seven phases. At the core of this approach is the process of reciprocal translation, where the key interpretations (termed ‘metaphors’) of included studies are juxtaposed with one another to enable new concepts to emerge. This protocol presents the first two phases, covering aspects of question formulation and search strategy utilising PICOS and STARLITE frameworks. We also present the protocol for the deeply interpretive analytical phases (four through six).

We provide a comprehensive rationale for undertaking a meta-ethnography, and throughout emphasise the way we intend to navigate the tensions in a predominately positivist systematic review and deeply interpretive nature of a qualitative synthesis. We discuss the issue of quality appraisal in qualitative syntheses and present a modified framework which will function to enable contextual interpretation and bring a sense of collective rigor, and detail why quality appraisal should not be used to exclude articles. Lastly, we highlight the reflexive nature of a meta-ethnography where the final findings are imbued with the researchers’ identity.

The field of simulation in healthcare continues to advance, yet a core facet of the learning process, debriefing, remains poorly understood. Whilst there is good evidence that debriefing is related to measurable outcomes in participants [1], the simulation literature is dominated by the descriptions of various debrief approaches or models [2] and methods to assess the quality of debriefing [3]. The structure of debriefing models is often a three or multi-phase approach [2] with a focus upon participant reflection during the analysis phase, based upon experiential learning theory (e.g. Kolb [4] and Gibbs [5]). The underpinning epistemological argument, as espoused by Mezirow (1990), is that learning occurs through the process of reflection, where perspectives are transformed, resulting in knowledge [6]. To deepen our understanding of how this educational intervention works and how it enables learning requires a shift of focus to clarification work, rather than on describing and justifying practice [7].

Research examining debriefing from the viewpoint of learners [8,9] and faculty members [10,11] has focused on experiences, suggesting factors such as a psychologically safe environment, the ability for faculty to explore thoughts, and the surfacing of different perspectives are all integral in the learning process. Although these factors are products of learner–faculty interactions, there is limited empirical research on the nature of these interactions: what are these interactions, how do these interactions occur and what relation do they have to participant learning? Debrief interactions can be examined from multiple perspectives, using methods of direct observation and video recording analysis, with the exact interactional focus dependent upon the researcher’s interest. By examining interactions, we can begin to understand how the process of debriefing is conducted and the ways in which it comes to be a learning experience.

This protocol outlines an empirical approach to bring together the existing debrief interactional research, adopting a process of discovering and formulating new knowledge in this field, achieved through a systematic meta-ethnographic qualitative synthesis. In the following sections, we detail the approach we intend to take and explain how a considered protocol can help traverse the tensions inherent in situating a more traditionally positivist systematic review approach alongside the deeply interpretative and reflexive qualitative synthesis. We believe there is merit in considering both perspectives and finding common ground between what traditionally have been considered binary positions, with an aim to facilitate the production of robust and rigorous research.

Although there are broadly similar published works relating to debrief interaction and learning for participants, the exact methods, foci of analysis and contextual factors differ across studies. Currently, studies provide little accumulated understanding of the topic but rather discrete knowledge blocks which are limited in their reach to the debriefing community. A qualitative synthesis aims to bring such isolated studies together to form new understandings of the field under scrutiny, to clarify inconsistencies, to inform practice and policies and to define future research agendas, particularly when the evidence is complex and is undertaken in different contexts [12–18]. The aim of a synthesis is to identify ‘what is known from multiple perspectives and reveal different factors, dimensions and explanations’ (p40) [19] for that existing knowledge, while also helping to illuminate a path for future research, practicum and scholarship.

Campbell et al. argue that when examining and synthesizing qualitative research, there is a risk of ‘destroying the integrity of individual studies’ and articulates a concern of ‘thinning out the desired thickness of particulars’ (p3) [12] – akin to a loss of context of the original studies [20]. Thus, to synthesize qualitative literature, particularly studies which form discrete knowledge blocks, the contextual elements during synthesis must be maintained. This is in part, because ‘meaning is sometimes inseparable from the data and not usually generalisable beyond it’ (p253) [21] unless readers engage in etic analysis.

Meta-ethnography, as an interpretative approach, maintains contextual elements whilst also mandating an emic approach to surface a ‘new interpretation or theory that goes beyond the findings of any individual study’ (p8) [12]. Noblit and Hare [22] first described this method in response to a failed attempt by others to synthesize original research on desegregation in schooling, where an aggregative approach resulted in the loss of the richness of the primary data and diluted the uniqueness of individual study sites. Taking a new interpretative stance, Noblit and Hare were able to demonstrate how new meanings can arise from seemingly similar studies by directing and undertaking a different analytic approach. Meta-ethnography enables new research questions to be identified and to ascertain the knowledge status of the field under study [12,20], and is thus an apt approach to explore the field of healthcare simulation debrief interactions.

Bearman and Dawson [21] argue that a qualitative synthesis relies on the series of expert judgements made by the researcher to enable conclusions to surface from the collective studies of interest. Indeed, meta-ethnography presents conclusions based upon the interpretation of the researcher – the judgement decisions the researcher makes are woven into the synthesis. Thus, to achieve new meaning, the process is deeply interpretative rather than aggregative [16]. This interpretative layer, formulated through seven phases as outlined by Noblit and Hare, extends beyond the original interpretation of the authors of the included studies [21], permitting the collective knowledge to be identified and progressed in parallel [12,23,24].

Noblit and Hare’s [22] original conception of meta-ethnography did not suggest the process of synthesis should be systematic, and the original formulation was constructed so a group of similar studies could be synthesized. Further supporting Noblit and Hare’s original position, Dixon-Woods et al. [25] and Toye et al. [26] argue that sampling should continue until theoretical saturation is reached; this indicates that the researcher has more control of what is included, guided to an extent by their interest. This may hold true where there is already a significant amount of published research in a field. However, in a relatively small and embryonic field, a point of saturation is unlikely to be reached.

To ensure we can identify as much of the published research as possible, to fulfil the aims of a meta-ethnography – which includes knowledge synthesis, identifying knowledge gaps and potential research avenues – it is prudent to employ a method to searching which is simultaneously comprehensive and manageable. It is here where frameworks traditionally used in positivist systematic reviews facilitate a structured approach to searching and article inclusion. Specifically, these frameworks typically include detailing a clearly formulated question with transparent and established frameworks for identifying, selecting, appraising and collecting data [27].

Positivist systematic reviews are further structured to ensure that analysis is undertaken in accordance with accepted standards; the approach is often clearly defined in logical sequential steps which are intended to be replicable, and transparency is conceptualized as the detailed documentation of procedures to enable reproduction of findings. It is here where there is perhaps the most clear departure with the theoretical basis of qualitative work. The systematic nature of a qualitative review is not related to (nor accepting of) positivist notions of the nature of knowledge and how knowledge can be synthesized. Instead, the concept of systematic here refers to the ways in which we decide how to search and what should be included in a review, and to make the process of undertaking a review manageable. It is systematic in that it uses accepted frameworks for this process, many of which have been used and continue to be used for qualitative work. There has also been a drive within the medical education community to improve standards of qualitative synthesis through the use of frameworks [17] in response to historic concerns of poor reporting [16]. We thus define transparency as detailing the explicit steps taken in question formulation, searching strategy and article inclusion decisions, and reporting in accordance with accepted guidelines. Current reporting guidelines include PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [27,28] and the recently published eMERGe guidance [29], which also overlaps with the ENTREQ statement (Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative research) [14].

Further, the protocol functions here not to argue that analysis is rigid, or is akin to following a recipe (a charge sometimes levelled against positivist work). Instead, it is to explicate the analytical steps of meta-ethnography, so the reader can follow the interpretative journey of the researcher, with cognizance that the researcher is deeply integral to analysis and the final research results are necessarily imbued with researcher decisions and identity. This demonstrates that the work undertaken aligns to the original ethos of Noblit and Hare’s seminal work, which we hope will provide the reader with a degree of confidence in the final interpretations produced.

In summary, the function of this protocol, and the intention of taking a systematic approach, is to be transparent regarding how the final articles selection came to be, explicating the intended analytical route – accepting the iterative and interpretative nature of the work – and presenting this in frameworks, including meta-ethnography-specific frameworks, which are advocated by the research community.

The aim of this review is to systematically search, examine and synthesize literature surrounding debrief interactions using a meta-ethnographic approach. The specific research question to be addressed through the synthesis is: How are interactions in simulation debriefing related to participant learning?

This will inform the community by:

The synthesis will be conducted aligning to the seven phases outlined by Noblit and Hare [22] which are presented in Table 1, with key practice points specified for each phase. This protocol fully addresses the first two phases, and elements of phase 3: data extraction fields and consideration of quality appraisal. The protocol also outlines the steps which will be taken in phases 4–6 and detail the intended analytical approach used in meta-ethnography.

| Phase | Key practice points |

|---|---|

| Phase 1: Getting started | Select & constitute research team Scope & research question Review registration |

| Phase 2: Deciding what is relevant to the initial interest | Search strategy Study selection: inclusion criteria Study selection: exclusion criteria Study selection: screening & PRISMA Flowchart Define quality appraisal framework |

| Phase 3: Reading the studies | Define data extraction fields Data extraction Quality appraisal Decide route of analysis± |

| Phase 4: Determining how studies are related | Analysis I: Grouping studies, identifying main metaphors |

| Phase 5: Creating reciprocal translations | Analysis II: comparing studies, developing new conceptual insights – ‘translations’ |

| Phase 6: Synthesizing translations | Analysis III: synthesizing translations* Analysis IV: develop line of argument+ |

| Phase 7: Expressing the synthesis | Conclusions I: presenting the findings Conclusions II: subjective and field interpretation of findings |

This table outlines the seven phases of meta-ethnography as originally stated by Noblit and Hare. We have detailed key practice points we intend to follow for each phase.

± Route of analysis: decide if the meta-ethnography is to be a reciprocal translation synthesis, refutational synthesis or line of argument synthesis or combination of above.

*Not essential if number of included studies is small and no disparate groups of translations.

+ Not essential if translations do not yield new information.

To undertake a transparent synthesis, each step must be clearly detailed and rationalized and the first step involves generating a research question [20]. Historically, as evident in Noblit and Hare [22], there has been little guidance on how to structure such question which will later serve as the basis for searching. The eMERGe guidance (criteria 3) requires a ‘well-defined’ and ‘focused’ question to be essential, especially for later stages, yet does not stipulate details on how it should be formulated [29].

Advocates of a systematic approach argue it should be structured within a standardized question framework and ensuring such formulation considers the contextual nature of the field [19]. Table 2 defines the research question according to the PICOS (population, intervention, comparison, outcome, setting) framework, which also forms the basis for both search terms (Table 3) and inclusion and exclusion criteria. Whilst this approach may have originated from positivist disciplines, the framework and utility are not tied to this realm; an indiscriminate approach may make it difficult to decide where and how articles should be searched for with a risk that the pool of potential articles generated being too small or too big.

| P | Population (who) | Simulation participants |

| I | Intervention (what) | Debrief |

| C | Comparison (against) | None |

| O | Outcome | Interactions associated with learning |

| S | Setting (context) | Healthcare simulation |

Research question presented in PICOS question framework.

| Simulation | Debrief | Interaction | Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulat* | Debrief* | Interact* | Learn* |

| scenario* | Conversation* | Know* | |

| train* | Observ* | Transform* | |

| discussion* | Outcome | ||

| Discourse* | behaviour* | ||

| Discursive | behavior* | ||

| Linguistic | chang* | ||

| ethno* | skill* | ||

| talk* | attitud* | ||

| question* | result* | ||

| narrative* | reflect* | ||

| stor* | |||

| Search string: (simulation* OR scenario* OR train*) AND (debrief*) AND (interact* OR conversation* OR observ* OR discussion* OR discourse* OR discursive* OR linguistic OR ethno* OR talk* OR question* OR narrative* OR stor*) AND (learn* OR know* OR transfer* OR outcome* OR behaviour* OR behavior* OR chang* OR skill* OR attitude* OR result* OR reflect*) |

The search terms have been derived from PICO question framework and a corresponding search string generated. ‘Setting’ (from ‘PICOS’) has been excluded from search terms so as not to inadvertently filter out relevant articles where ‘healthcare’ is not included. This is considered in the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Reviews are often conducted in teams of two or more individuals; to maximize efficiency and to increase rigor. Within meta-ethnography, there are differing perspectives regarding individual and collaborative approaches, especially when the number of potential studies to be included is anticipated to be high [28]. Considering the process of meta-ethnography is deeply interpretative, the work should be seen as original research. As such, and in keeping with Noblit and Hare’s approach [22], this synthesis will be undertaken with a researcher and supervisor team (authors of this protocol).

This phase explicates our focus of the synthesis by listing the inclusion and exclusion criteria and undertaking a process of searching, screening and appraising literature [28]; the intention is to be transparent about how articles have been included and why [30], and has been advocated in eMERGe guidance [29]. The STARLITE mnemonic (Table 4) was devised based upon a systematic review conducted by Booth [30] examining the reporting of searches within systematic qualitative reviews; its construction, based upon a systematic literature review, is robust and its utility is demonstrated in this context.

| S | Sampling strategy | Comprehensive search: peer-reviewed articles only |

| T | Type of studies | Qualitative research with analysis of naturalistic data Studies focused on debrief interaction captured via: • participant observation • video recording • audio recording |

| A | Approaches | Electronic searches (see list below) Citation snowballing Hand-searching following journals: • Simulation in Healthcare • Advances in Simulation • BMJ Simulation & Technology Enhanced Learning • Clinical Simulation in Nursing |

| R | Range of years | No limits applied |

| L | Limits | Functional limits: humans, subjects aged 18 or over, full-text availability |

| I | Inclusion and exclusion criteria | See Tables 5 and 6 |

| T | Terms used | See Table 3 |

| E | Electronic sources | • British Education Index (BEI) • CINAL • Cochrane • Education Abstracts • ERIC • ERICESCBO • ProQuest • PubMed • SCORPUS • Web of Science |

The search strategy is detailed using the STARLITE framework.

The criteria for inclusion and exclusion (Tables 5 and 6) should begin with the original question in mind and should be structured based upon the domains of interest [17]. The field of empirical debrief interaction research remains primitive, and thus it is important to include all published studies, irrespective of the publication date. Whilst synthesis methods exist for the interpretation of studies with different methodologies, there is an inherent risk of weak conclusions being drawn from data which is generated from different epistemological positions [20,25]. For this reason, interpretive data using methodologies aligned with such different positions will be excluded; only interaction analysis studies are included.

| Inclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| All languages | Emerging field; important not to exclude studies which are potentially influential Considering analysis is based on second-order constructs, if these are in another language, they can be translated whilst preserving meaning. |

| All date range | Emerging field; important not to exclude studies which are potentially influential |

| Peer-reviewed journals | Keep the process of searching systematic, rigorous and manageable |

| Conference proceedings | Emerging field; important not to exclude studies which are potentially influential Full-text search for abstracts identified will be performed |

| Simulation-related debriefing | Scope is limited to simulation; excluding other industries and clinical debriefing |

| Undergraduate and postgraduate participants | Emerging field; important not to exclude studies which are potentially influential Reflects simulation practice; simulation is available to both undergraduate and postgraduate courses |

| Faculty of all experience | Emerging field; important not to exclude studies which are potentially influential Reflects simulation practice; simulation is facilitated by educators of varying experience |

Study inclusion criteria and corresponding rationale.

| Exclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Full text not available | Unable to gather full details of methods, analysis or results |

| Conference proceedings without corresponding article* | Outside scope of research; conference proceedings are excluded |

| Non-simulation debriefing | Outside scope of research; debriefing only related to simulation included |

| Simulation event analysis | Outside scope of research; focus is on debrief, not simulation event |

| No debrief interaction analysis* | Lack of interpretative data; analysis of naturalistic data must occur |

| Non-healthcare simulation debriefing | Outside scope of research |

| Debriefs involving patients contributing to the discussion | Atypical simulation debrief; ethical issues |

| Debrief focused on CSID/reducing PTSD | Atypical simulation debrief; ethical issues |

| Classroom size debriefs (c. >20) | Atypical simulation debrief |

| Single faculty single participant debrief* | Atypical simulation debrief |

| Theoretical articles | Lack of interpretative data |

| Content analysis | Lack of interpretative data |

| Exclusively interview/focus group-based study | Analysis of naturalistic data must occur |

| Methods not reported/unclear* | Unable to gather full details of methods, analysis or results |

| Outcomes not stated | Unable to gather full details of methods, analysis or results |

| Partial/incomplete data reporting± | Unable to gather full details of methods, analysis or results |

| Survey studies/data | Analysis of naturalistic data must occur |

| Document analysis | Outside scope of research; focus is on debrief interaction |

| Analysis for purpose of evaluation | Outside scope of research; focus is debriefing for learning |

| Studies involving participants < 18 years of age | Atypical simulation debrief; ethical issues |

| Faculty only debriefs | Atypical simulation debrief; data must include faculty–participant interactions |

| Participant only debriefing (e.g. self-debriefing) | Atypical simulation debrief; data must include faculty–participant interactions |

| Non-face-to-face debrief (i.e. virtual reality, distance or tele-debriefing debrief) | Atypical simulation debrief |

| Descriptive study (e.g. course or debrief description)* | Lack of interpretative data; analysis of naturalistic data must occur |

| Debrief assessment using tools* | Outside scope of research. |

Study exclusion criteria and corresponding rationale; CSID, critical stress incident debriefing; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; ± includes different types of data grouped during analysis.

*Denotes criteria added or modified after initiating initial searches.

Sawyer et al.’s [2] non-systematic literature review of debrief practice concluded that facilitator-guided post-event debriefing was the most reported method. If this then represents the community’s perspective on ‘ideal’ debrief practice, it is prudent, to further our knowledge in this field, to synthesis literature based around the practice which is occurring internationally. For example, debriefs involving participants numbers exceeding c.20 are excluded, as the conversations and interactions at this level are likely to be very different to those seen more commonly in smaller groups [31]. Similarly, the field of virtual reality and online debriefing have only recently emerged, and these represent different interactional approaches. The exclusion criteria ensure that papers with common ground are selected, as this is central to meta-ethnographic work [32].

Study appraisal is an essential step when combing primary data in a meta-analysis, to be aware of and to exclude from the results studies that are likely to have a significant bias. This step of excluding articles via virtue of a scoring system is not recognized in the same way in meta-ethnography. This is primarily because, as Noblit and Hare state, ‘the issue of judgements and biases is accepted and included in the account created’ (p35) [22]. Secondly, there is heterogeneity in the types of data, ranging from thick descriptions in ethnographies to detailed transcribed data in conversation and discourse analytic studies. Similarly, the data captured and analysed in different studies is not intended to be comparable, considering that ‘studies often explicitly set out to examine restricted aspects of a phenomenon, practice or domain in great depth’ (p8) [31].

We aim to take a similar stance in this synthesis to Campbell et al. [12] and Dixon-Woods et al. [25], who advocate for a clear description of methods, since these are directly related to author interpretations. If studies fail to detail their methods of data collection and analysis, or if the mechanism by which the authors came to their interpretations is unclear, then these will be excluded from the synthesis and will be stated in the exclusion criteria.

It is still valuable however, to conduct formal quality appraisal after papers have been screened and selected; this is not to exclude studies (as in positivist systematic reviews), but instead to facilitate deeper understanding. This is prudent in this synthesis, where single studies may have significant influence on the researchers’ interpretation. Thus, a more suitable approach, and one we will employ here, is to use quality criteria to detail studies’ relevant attributes and how they are related to the subsequent interpretation of these studies; quality criteria will not be used to exclude studies. Such an approach is supported by Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group, who warn against the use of scoring systems and arbitrary cut-offs. and instead to use the quality appraisal process to interpret the findings of the review [33]. The function, then, of quality appraisal is two-fold: to provide additional information for the meta-ethnographic researcher which may contribute to their interpretations of that individual study, and the relation and interpretation to other papers during the synthesis; and, secondly, to provide the reader of the meta-ethnography with additional contextual information that may influence their own reading.

The Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group highlight the CASP (Critical Skills Appraisal Programme) tool as the framework used for Cochrane guideline process [33,34] and use of this in meta-ethnography is advocated by others [12,14,17,20]. The Joanna-Briggs Institute has also developed checklists to appraise different types of studies [35], with a specific checklist for qualitative research (JBI-QAC). This has similarities with the CASP tool and offers additional criteria that examine congruity between philosophical positions, methodology, methods and the research questions. The JBI-QAC framework also prompts the researcher to provide additional details which would be omitted if the CASP tool is solely relied upon, for example, details regarding reflexivity and author-cited limitations. Therefore, to ensure detailed coverage, the two frameworks have been combined in a modified quality appraisal framework, which contains additional fields optimized for and applied to this research.

‘Additional File 1 – Quality’ presents the modified framework (Tab A) and the appraisal template (Tab B).

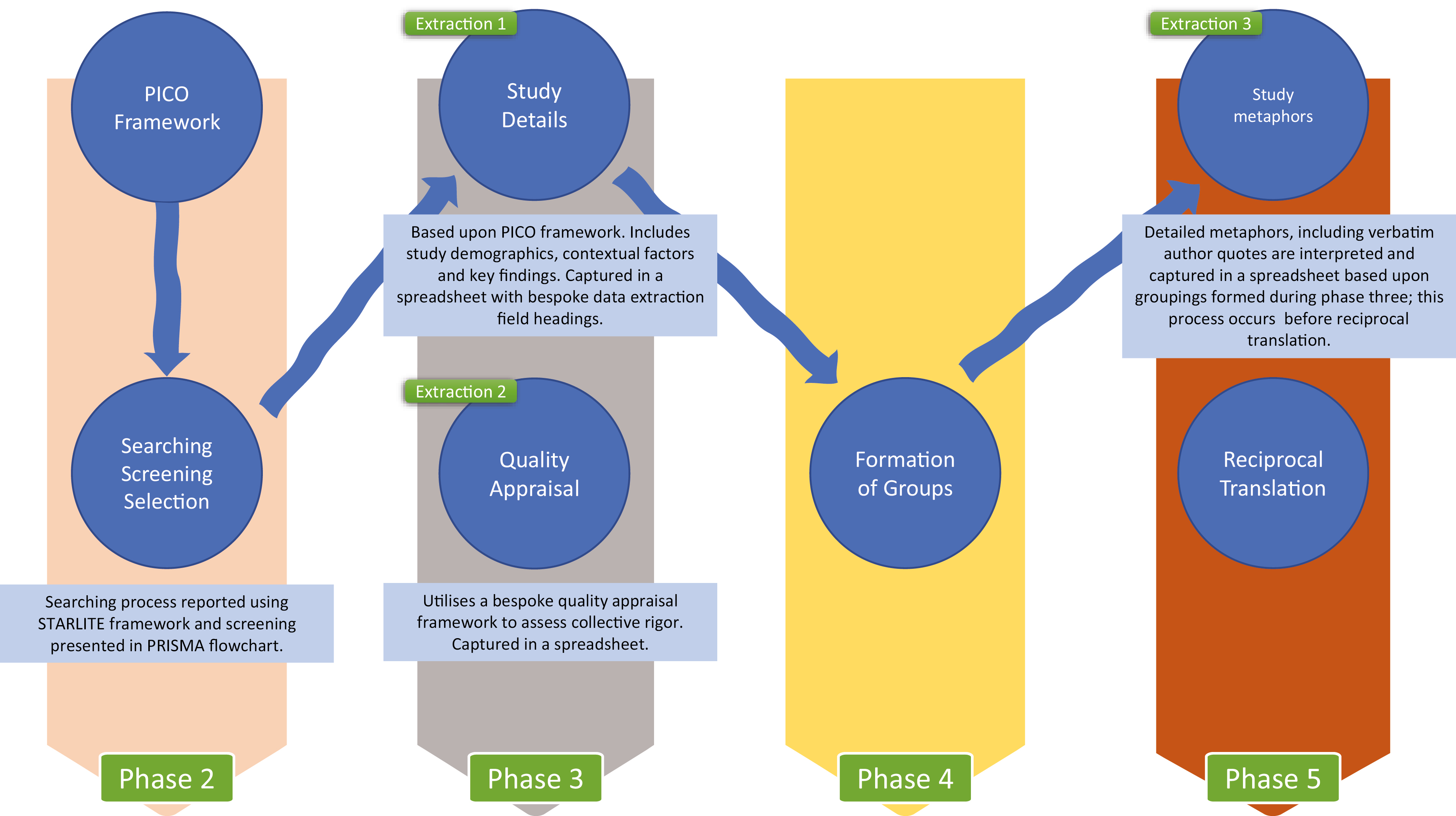

Noblit and Hare [23] argue that for the researcher to become sensitive to the detail of the text and to be able to extract the meaning, multiple readings are required. Multiple readings of the same article are achieved inherently: firstly, upon selecting for inclusion in the synthesis; a second time to highlight key aspects; detailed reading during the third time to extract study details including contextual elements [24]; a fourth time to extract data relating to quality appraisal; the fifth time when identifying, extracting and interpreting metaphors; then further readings when translating studies into one another. These multiple readings serve to allow the researcher to view the text from different perspectives, thereby surfacing different readings [22,28] whilst simultaneously preserving the context when data is being extracted [20]. Figure 1 outlines these three distinct data extraction episodes: the first involves extracting study details, contextual factors and key features; the second is extracting data for quality appraisal; and the third involves extracting data in the form of metaphors, undertaken in preparation for reciprocal translation in phase 5. It is important to note here that the process of extraction is, itself, a form of interpretation, and marks the interpretative work involved in meta-ethnography.

Data extraction episodes.

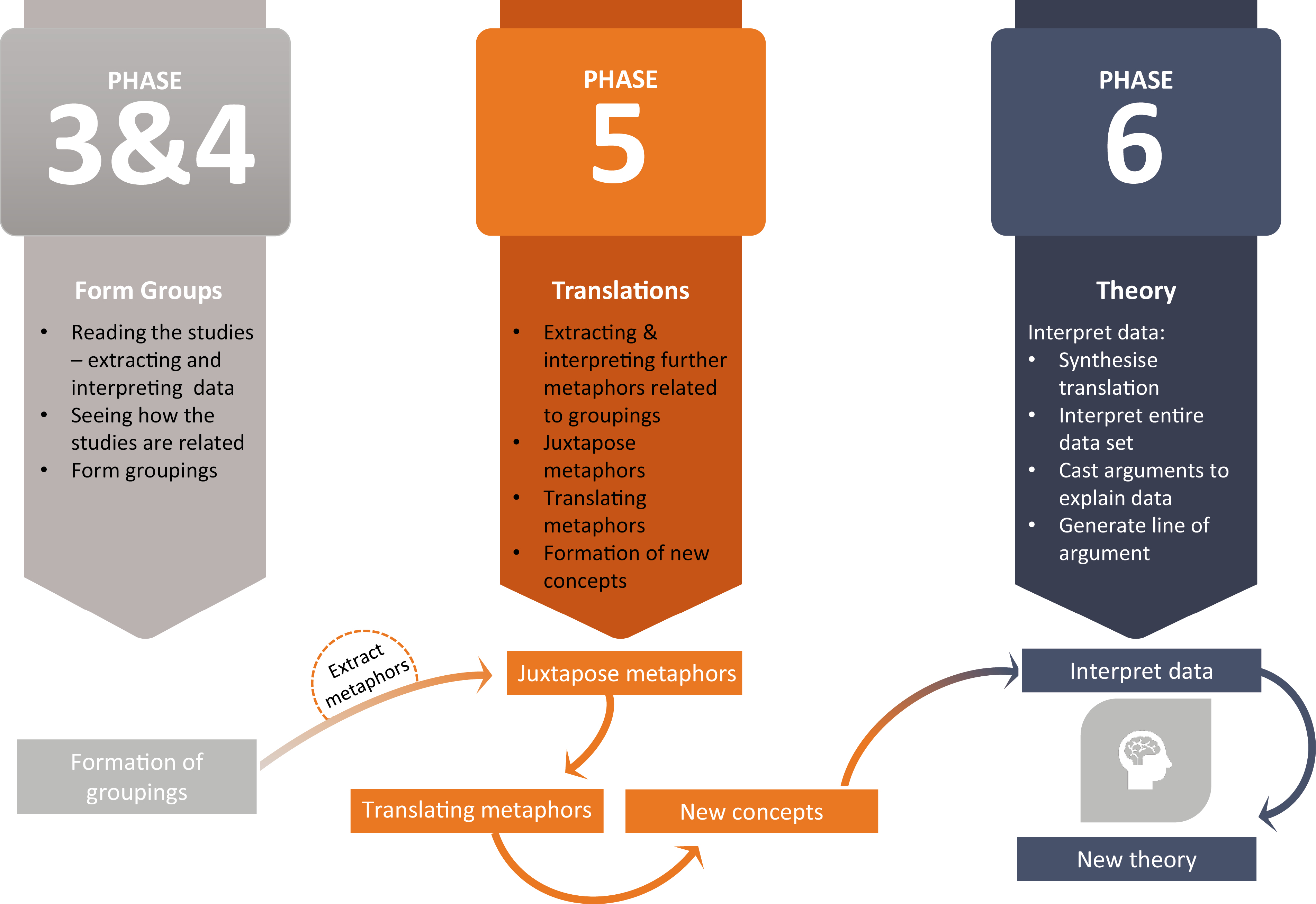

Analytical steps.

There is no consensus of best practice for data extraction and management in meta-ethnographies. Atkins et al. have used standardized forms for collecting information regarding main themes, methods, quality and details of ethics [20]. Parry and Land [31], when undertaking a synthesis of conversation analysis studies, focused on the type and amount of data, and the detail and depth of data analysis reported. It is critical that as much detail as possible is extracted from the primary studies, so as not to lose the context in which the results are interpreted [33]. As such, a data extraction template (see Table 7 for data extraction fields) will capture both second-order constructs and detailed contextual factors [12].

| Paper details | Author; year; journal; language; study period; country research conducted; study aim(s)/question(s); study background |

| Participant Demographics | Speciality; undergraduate/postgraduate; year; ages; sex (number); simulation experience |

| Faculty Demographics | Speciality; experience; sex (number); ages |

| Simulation Course Details | Simulation modality; simulation description; number of participants/courses; number of participants/simulation event |

| Debrief Details | Number of faculty/debrief; debrief model/approach; debrief time/session; video use in debrief; debrief number |

| Method and Analysis Details | Data capture method; secondary data capture method; total debrief time; transcription details; materials transcribed; analysis method |

| Study Findings | Main findings; additional findings/author conclusions |

| Limitations/Reflexivity | Author-cited limitations; identified limitations |

| Miscellaneous | Additional notes; further references to review from bibliography (for citation snowballing) |

The data extraction fields are specific to the types of research included and centred around simulation-based education demographic details. Data will primarily be captured in phase 3.

A key component of the synthesis is to understand how studies are related to one another, and more specifically, how the interpretations one author makes of the phenomenon in question is similar or different to that of other authors [12]. Noblit and Hare label these connections as assumptions [23] and these are surfaced based on common or frequently occurring metaphors [24]. Thus, phase 4 will be concerned with specifying what these connections are and identifying the main groups.

Phase 5 will be conducted in line with Noblit and Hare’s original framework, which offers an option to take one of three different approaches: reciprocal translation (when studies are similar); refutational synthesis (when studies implicitly or explicitly refute each other); and, line of argument synthesis (when studies build a larger theory of an issue) [22]. Reciprocal translations also form the first phase of a line of argument synthesis (phase 6). Thus, a line of argument, in accordance with Noblit and Hare’s approach, is a second phase of analysis. It is here, where Britten et al. argue that the line of argument is a ‘middle-range theory’ (p214) [24] achieved by ‘…making a whole into something more than the parts alone imply’ (p28) [22] which France et al. (2019) state, after consultation with Noblit, produces ‘a new “storyline” or overarching explanation of a phenomenon’ (p10) [32].

Since inception, this framework has evolved, and recently France et al. (2019) have stated that researchers should actively seek to undertake both reciprocal and refutational analysis (which they also label as ‘deviant’ data) in heterogenous studies, as this facilitates a fuller understanding of the phenomenon [32]. France et al. (2019) [32] have provided further guidance on the analytical phases, echoing Noblit and Hare’s stance that the process is iterative with overlapping phases. Such an iterative approach is not restricted to meta-ethnographies and is seen as a key principle in other qualitative synthesis methods [33]. The key aspect of this approach is to derive meaning from multiple cases in a systematic and transparent approach [21], ‘relating knowledge and showing its relevance in establishing its meaning’ (p99) [23].

The knowledge units to be synthesized, through a process of interpretation, in meta-ethnographies are the interpretations of individual study authors . These ‘interpretative explanations are narratives through which the meaning of social phenomena are revealed’ (p101) [23]. The translations of these produce new meanings and have been defined as third-order constructs [12]. It is beneficial here to ponder the power of using Schutz’s [36] definition of constructs, which is often accepted without deliberation within meta-ethnographic work. This is eloquently summarized by Toye et al.:

Schutz makes a distinction between (1) first order constructs (the participants’ ‘common sense’ interpretations in their own words) and (2) second order constructs (the researchers’ interpretations based on first order constructs) (p7) [26].

In simulation debriefing, the ongoing interactions and actions by actors involved (participants and faculty) are driven by their own constructs. These are then interpreted by authors of included studies; these interpretation are then defined as second-order constructs. These constructs may be presented in various ways: in narratives, tables, figures, or distinct thematic or conceptual descriptions. Whatever form they take, the authors attempt to transfer knowledge, usually metaphorically, using language. There are often different words used to describe this knowledge in the literature, such as theme, concept, and what Noblit and Hare term ‘metaphor’ [22]. Campbell et al. [12] argue that there is a need for consistent language and therefore, it seems prudent to adhere to a single label for the underlying phenomena. In interpretivist research, authors describe their researched interest: ‘in short, interpretation, as a form of communicated knowledge, is symbolic and thus metaphoric’ (p33) [22]. Thus, we argue that metaphor is the most appropriate term and will be used in our research.

Phase 5 is therefore concerned with examining the main metaphors from each study within each of the groupings from phase 4. Analytically, a grid will be created to allow metaphors to be juxtaposed: metaphors from each study will be examined in relation to other studies – the hallmark of reciprocal translation – and to generate third-order constructs [14,26]. A similar process is undertaken if there is evidence that refutational translation should be undertaken.

It may be apparent that some of these new concepts will be closely related, to the extent that they can be further synthesized (beginning of phase 6). The synthesized translations, and those translations from phase 5, can then be viewed and interpreted in relation to one another. The task here is to cast an explanation over the entire data set (line of argument) and thereby generate new theory. This analytical process in relation to phases 4 through 6 is outlined in Figure 2.

Importantly, the process of extracting data in a meta-ethnography differs from that in a meta-analysis. The process does not claim to be neutral, but rather is fundamentally interpretive: decisions are made by the meta-ethnographer of what is of interest, how it is captured (indeed, the very transformation of which inevitably involves a form of interpretation), and how that data is subsequently managed. All these are inextricably linked with the researcher, and we intend to share, as far as possible, the analytical steps we take with the reader.

Whilst meta-ethnography is an established synthesis method, particularly in relation to health policy, previous meta-ethnographies have been critiqued as being poorly reported. The function of this protocol is to detail some of the choices made, and the underlying rationale of, a planned meta-ethnography of debriefing in healthcare simulation, building on the original framework of Noblit and Hare. The final phase of the meta-ethnography is to present and interpret findings, including possible new theory that is generated, in relation to existing research and the simulation community.

The core tenet of meta-ethnography is the interpretative work undertaken by the researcher; the work cannot be excised from the researcher. As such, it is important that the final meta-ethnographic work acknowledges this, and we will explicitly include researcher reflexivity, something which has often been lacking in published meta-ethnography work [12] yet is considered an essential reporting item in meta-ethnographies [29] and integral for rigor [26].

There are now substantial numbers of published systematic meta-ethnographies in healthcare, which often do not explicate some of the decisions taken nor the rationale for using frameworks and approaches. The intention of this protocol is to explicate how we intend to navigate some of the tensions between two often conflicting territories, to produce a thorough and rigorous analysis which will inform both theory and practice.

Supplementary data are available at The International Journal of Healthcare Simulation online. ‘Additional File 1 – Quality Framework.xlsx’ contains the following: Modified Quality Framework – Tab A; Appraisal Template – Tab B.

Dr. Anne McKee provided supervisory support to the first author.

The field of interest, choice of synthesis approach, research question and search strategy were agreed by both authors. RK wrote the manuscript. Both authors reviewed, edited and agreed the final manuscript.

No funding declared.

Not applicable.

Ranjev Kainth declares no competing interests. Gabriel Reedy is affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emergency Preparedness and Response at King’s College London in partnership with Public Health England (PHE), in collaboration with the University of East Anglia and Newcastle University. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health or Public Health England.

RK is currently undertaking a PhD in medical education focused upon simulation debriefing. This submission forms part of the overall thesis. GR is the primary academic supervisor.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.