First, to determine the feasibility of providing a simple educational intervention using the HEEAL (Honesty, Empathy, Educate, Apology/awareness, Lessen the chance for future errors) mnemonic. Second, to assess the intervention’s ability to improve communication self-efficacy, knowledge and objective measures of error disclosure competence among providers.

A 1-day (6-hour) pilot medical error curriculum was created to teach the HEEAL method of medical error disclosure to both patients and peers who have committed errors. The four-part curriculum consists of pre-intervention evaluation, HEEAL content lecture, rapid cycle deliberate practice (RCDP) with debriefing and post-intervention evaluation. This curriculum was repeated twice. The first training focused on medical error disclosure to patients’ families and the second on medical error disclosure to involved peers. Participating faculty developed, adapted and piloted simulation cases, skills checklists and knowledge questionnaires. The barriers to error disclosure assessment (BEDA) tool served as our confidence survey. Five additional questions developed and piloted by the research team were administered with the BEDA to assess learner confidence with peer–peer disclosure. Pre- and post-intervention written measures of knowledge and confidence (BEDA) were obtained for both iterations of the curriculum. Assessment of observed clinical skills was scored by the involved SP (standardized patient) immediately following the RCDP. An a priori Kappa coefficient of <0.9 was used to measure SP scoring reliability.

Fourteen learners completed all curricular components. Learners demonstrated statistically significant improvement in their confidence in medical error disclosure (p = <0.0001), knowledge (p = 0.0087) and performance of peer-disclosure skills (p = 0.001). Participants demonstrated improvement in (p = 0.05) patient-disclosure skills, yet this skill did not meet statistical significance.

This pilot data suggest that the HEEAL intervention provides an effective and efficient way for medical educators to teach senior medical students how to provide competent error disclosure to both patients and peers.

In 2000, an Institute of Medicine report on medical error sparked a national dialogue on healthcare safety [1]. Two decades later, a new report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has implicated the emergency department in an error rate that impacts 1 in 18 patients and results in 2.6 million adverse events annually, with 370,000 of these producing serious harm and more than a quarter of million deaths [2]. These rates and the surrounding controversy demonstrate that in medicine, error is a problem that has yet to be solved.

One major error management strategy focuses on transparency surrounding error events, including disclosure of medical errors to affected patients and families [3,4]. In 2001, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations required disclosure of all patient care outcomes, including ‘unanticipated outcomes’, as part of its accreditation standards for hospitals and healthcare organizations [5]. In 2006 and 2010, the National Quality Forum endorsed new guidelines concerning unanticipated patient care outcomes. These guidelines outlined the basic content of the disclosure discussion, including providing facts about the event, expressing regret for unanticipated outcomes, and apologizing if an error was the cause of the adverse event [6,7].

Although these disclosure guidelines and standards exist [8,9], there remains no universally adapted rubric for teaching medical professionals to communicate medical errors to patients, families and other physicians [10–12]. Because informing patients, families and colleagues of a medical error is a difficult task, in which physicians have limited experience and have little formal training, many physicians lack confidence in conducting difficult conversations [13,14]. Studies suggest [15,16] that a major barrier to disclosure is the uncertainty of healthcare providers regarding how much, as well as the content of, information to share with patients, families and peers after an error has occurred [13,14]. While there has been previously published scholarship in this area [17–19], specifically towards disclosing information to patients and families, this novel curriculum includes a framework for how to disclose errors to peers in a method that potentially minimizes the negative impact a physician might feel when they are ultimately informed a patient had a suboptimal outcome that involved an error their management. To address this gap, we developed a simple mnemonic, ‘HEEAL’, which addresses the key elements of an error disclosure (Honesty, Empathy, Education, Apologize/awareness, Lessen future impact) to provide structure to the communication encounter. This pilot study utilized volunteer students in their final year of medical school, during a ‘Transitions to Residency’ rotation. We believe this is the ideal learner group for this curriculum as they have a basic understanding of clinical experience and will be expected to perform this skill in a few short months, but have not yet been asked to lead serious conversations with their patients.

The purpose of this study was twofold. First, to determine the feasibility of providing a simple educational intervention using the HEEAL mnemonic. Second, to assess the intervention’s ability to improve communication self-efficacy, knowledge and objective measures of error disclosure competence among providers.

The Indiana University School of Medicine institutional review board classified this pilot pre–post educational intervention as exempt. This study was performed in January 2021 at a tertiary-care, university-affiliated teaching hospital simulation lab with audio and video recordings.

Fourth-year medical students at Indiana University School of Medicine were invited to participate. Audio and video recordings and data collection were supervised by two standardized patient coordinators. Inclusion criteria included all 4th-year Medical Students in good standing with the university who were free from other clinical responsibilities during the study period.

A 1-day (6-hour) pilot medical error curriculum was created to teach the HEEAL method of medical error disclosure to both patients and peers who have committed errors. The lead author created the mnemonic, and the curriculum was designed by faculty with expertise in medical simulation, medical malpractice, assessment and communication competency. Two of the coauthors are Professors of Emergency Medicine with over 100 peer-reviewed publications each and extensive experience in developing novel curricula. The four-part curriculum consists of pre-intervention evaluation, HEEAL content lecture, rapid cycle deliberate practice (RCDP) with debriefing and post-intervention evaluation. This curriculum was repeated twice during the 6-hour course. The first training focused on medical error disclosure to patients’ families and the second on medical error disclosure to involved peers.

Participating faculty developed, adapted and piloted simulation cases, skills checklists and knowledge questionnaires. The BEDA tool (used with permission) served as our confidence survey [20]. Five additional questions developed and piloted by the research team were administered with the BEDA to assess learner confidence with peer–peer disclosure.

Pre- and post-intervention written measures of knowledge and confidence (BEDA) were obtained for both iterations of the curriculum. Assessment of observed clinical skills was scored by the involved SP (standardized patient) immediately following the RCDP. Fifteen per cent of encounters were scored by course faculty and compared to the SP score as a measure of inter-rater reliability. An a priori Kappa coefficient of <0.9 was used to measure SP scoring reliability. Pre- and post-intervention tools were identical.

For all simulations, trained SPs acted as patient family members or peer physicians. Standardized patients underwent a 4-hour training to ensure consistency of case performance and skill assessment. To ensure realistic scenarios and limit confounders, each learner encountered a different SP for each case during the trainings and assessments. A total of 13 SPs were included in this case: 8 formally trained SPs served as family members in the morning cases and 5 formally trained peer-aged SPs, and 3 simulation-trained peer-aged physicians performed in the afternoon cases [21,22]. All debriefing faculty attended an RCDP rehearsal with the study team to teach the RCDP feedback method and the proper use of the HEEAL mnemonic. RCDP is a simulation-based instructional strategy that focuses on rapid acquisition of clinical skills in a small group where the faculty member frequently stops the simulation, provides actionable feedback to the student(s), ‘rewinds’ the scenario and provides an opportunity for the student(s) to demonstrate the feedback has been understood and is observable in action during the scenario. This can occur several times during a scenario until the faculty member can observe all desired critical actions in practice with minimal feedback [23,24]. All simulations and RCDP debriefings were audio and video recorded, and data collection was supervised by two standardized patient trainers.

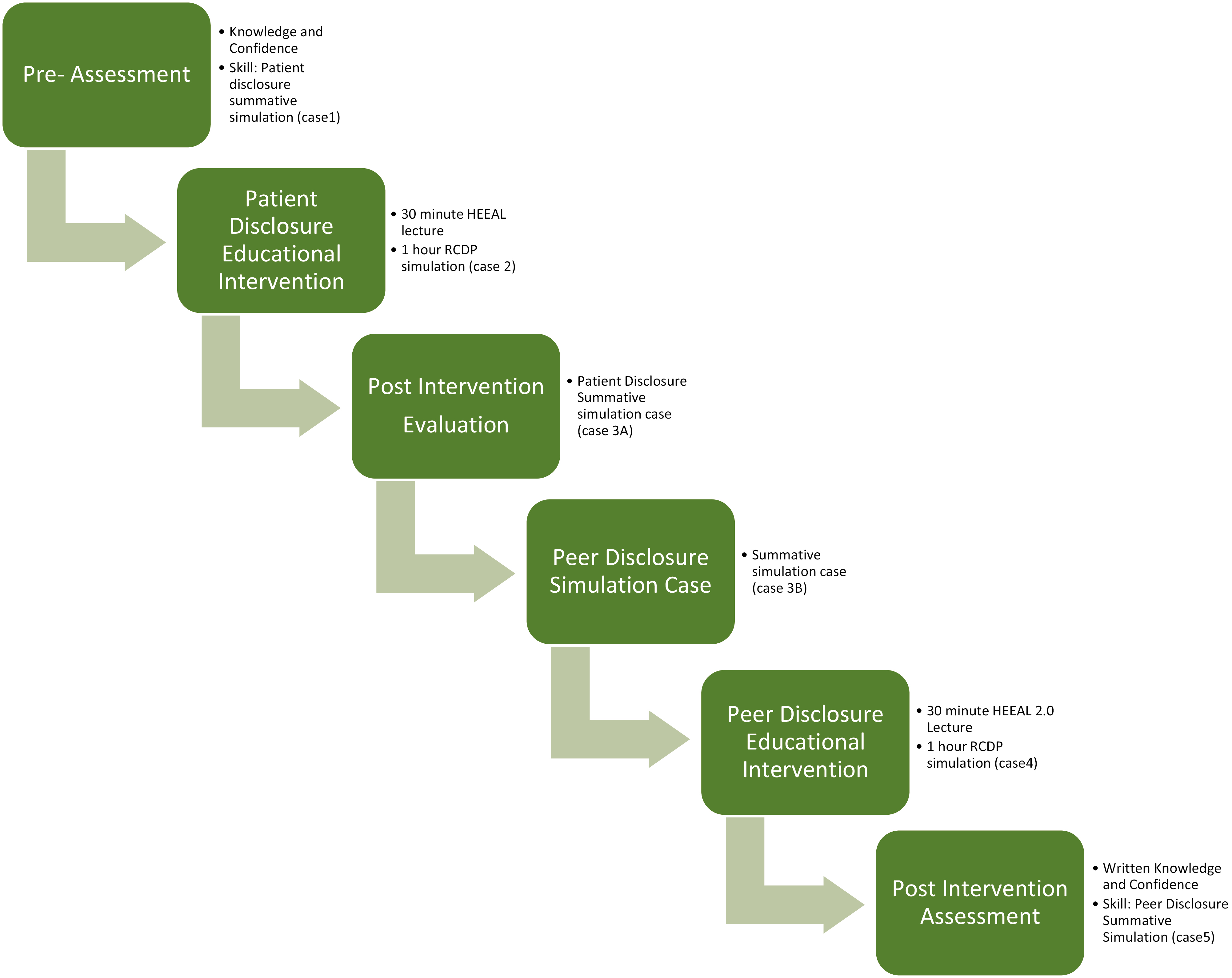

The study sequence is outlined in Figure 1.

Study sequence. RCDP, rapid cycle deliberate practice.

The learner’s pre-intervention evaluation assessed baseline knowledge and confidence using a multiple-choice test and the modified BEDA instrument. Skill assessment was measured in a summative simulation case (Case 1: Wrong Medicine), in which a patient was given a medication to which they were documented to be allergic. Individual learners were assigned to a room and provided with a ‘door note’ containing the case materials, including the patient’s medical chart, the medical error and the subsequent course of events. This note was also available for reference during the simulation. No feedback was given to participants during the pre-intervention assessment phase.

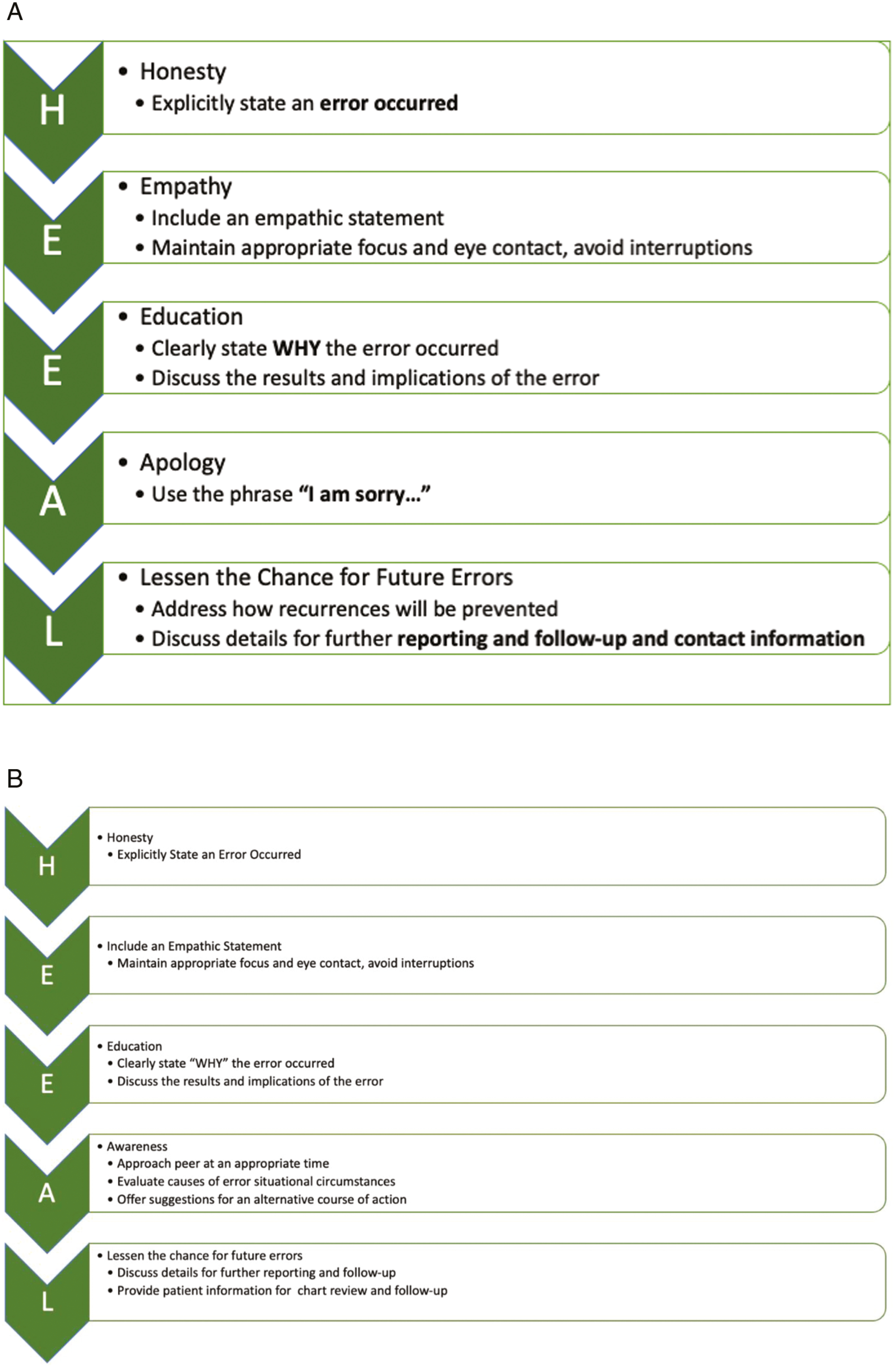

Immediately following the pre-intervention evaluation, students attended a 30-minute medical error disclosure lecture where they were introduced to the HEEAL mnemonic as a method for error disclosure. Small groups of students (2–3 per group) then participated in a 1-hour RCDP formative simulation case (Case 2: Inappropriate Medicine). Learners were provided a HEEAL reference card to review when observing other students actively participating in an RCDP error disclosure (see Figure 2A).

HEEAL mnemonic for use in disclosing errors to (A) patients and (B) peers.

Learners completed a summative simulation case (Case 3A: Missed/Delayed Diagnosis, Patient), graded by the SPs.

Following their summative simulation case, learners then immediately went into a subsequent summative simulation case (Case 3B: Missed/Delayed Diagnosis, Peer). This case introduced the concept of disclosing medical errors to colleagues. Learners then received a 30-minute didactic on HEEAL 2.0 and a formative RCDP scenario (Case 4: Misdiagnosed Sign-Out). Learners were provided a HEEAL reference card to review when observing other students actively participating in a RCDP error disclosure (see Figure 2B).

Immediately following this educational intervention, learners completed the final peer disclosure summative simulation (Case 5: Inaccurate Sign-Out). This was followed by the same multiple-choice test and confidence survey provided at the beginning of the curriculum. To evaluate change in skills, SPs graded the final summative cases in real time.

Upon completion of the multiple-choice and confidence surveys, learners were invited to complete a post-curriculum survey consisting of nine open response questions. This included assessment of the strength, limitations and effectiveness of the curriculum content, and assessment, timing and group sizes.

To estimate differences between pre-and post-intervention scores, a Wilcoxon test was utilized. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using a simple kappa coefficient. SAS Version 9.4 was utilized to complete all statistical analyses.

Fourteen learners completed all curricular components. Of these, 3 had previously disclosed an error to a patient, and 10 had disclosed a peer’s error to the peer. Learners demonstrated statistically significant improvement in their confidence in medical error disclosure (p ≤ 0.0001), knowledge (p = 0.0087) and performance of peer-disclosure skills (p = 0.001). Participants demonstrated improvement in (p = 0.05) in patient-disclosure skills, yet this skill did not meet statistical significance (Table 1). As expected, there was no improvement in confidence related to barriers to error disclosure. This typically cannot be resolved via an educational intervention. Our inter-rater reliability of learner evaluations demonstrated fair agreement for patient and peer disclosure (Table 2).

| Curricular Evaluation | Pre | Post | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient sum (performance evaluation by SPs) | 19.0 (16.0–22.0) | 21.0 (16.0–23.0) | 0.0526 |

| MCQ | 8.0 (6.0–9.0) | 9.0 (7.0–10.0) | 0.0087 |

| Peer sum (performance evaluation by SPs) | 14.0 (10.0–17.0) | 17.0 (13.0–18.0) | 0.0010 |

| BEDA 1 (Perceptions) | 45.5 (39.0–50.0) | 55.5 (50.0–63.0) | <0.0001 |

| BEDA 2 (Barriers) | 27.5 (12.0–54.0) | 29.0 (16.0–60.0) | 0.4613 |

| Confidence | 19.5 (15.0–26.0) | 32.0 (26.0–38.0) | <0.0001 |

BEDA, Barriers to Error Disclosure Assessment; SP, standardized patient; MCQ, multiple-choice questionnaire.

*Estimated using Wilcoxon test

| Estimate* | 95% Confidence Limits | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient sum (performance scoring by SPs) | 0.38 | 0.17–0.60 |

| Peer sum (performance scoring by SPs) | 0.33 | 0.13–0.53 |

*Estimated using simple kappa coefficient.

We separately analysed our add-on questions from the previously validated BEDA tool and identified (statistically significant) improvement in confidence specifically for peer-to-peer disclosure (Table 3).

| Pre | Post | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) or Median (Min–Max) | N (%) or Median (Min–Max) | P value* | |

| Indicate your degree of agreement with the following statements (5 – Strongly Agree, 1 – Strongly Disagree) | |||

| I am confident in my ability to disclose a peer’s medical error to that peer. | 3.0 (1.0–4.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 0.0061 |

| I am not sure of the etiquette to disclose another colleague’s error to that colleague.** | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | <0.0001 |

| To what degree do the following pose a barrier in your ability or willingness to disclose an error? (5 – Very much a barrier, 1 – Not at all a barrier) | |||

| Fear of damaged relationship with peers | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–5.0) | 0.3327 |

*Estimated using Wilcoxon test.

**Reverse coded.

In regards to the overall evaluation of the curriculum from the learner’s perspective, it received very positive feedback for the use of the RCDP technique in the training of the skill of error disclosure.

There were several requests to include this in the formal curriculum for the medical school. Additionally, students desired feedback from the SPs after their summative cases to gain a better perspective of their performance from the patient’s viewpoint.

Students were invited to provide an anonymous evaluation of the course at its completion. All learners completed the evaluation, and the comments were transcribed into an Excel sheet for review. Feedback was overwhelmingly positive. When asked about the greatest strengths of the curriculum, one learner stated, ‘I liked the HEEAL acronym and the live feedback received [during] cases were challenging but [a] great learning opportunity’. Multiple students appreciated that this curriculum filled a self-identified knowledge gap. Organizing the curriculum so that learners reviewed the mnemonic through lecture and then practised the conversation in an RCDP manner was listed as the greatest strength by several learners. Multiple learners expressed the desire to incorporate this boot camp into their formal medical school curriculum.

HEEAL may help to alleviate provider uncertainty by introducing a systematic approach to the type and quality of information conveyed when disclosing an error to patients and peers.

This study yielded three important findings. First, the HEEAL training method effectively improved error disclosure communication skills in medical students. Second, the training improved student communication self-efficacy, knowledge and competence in disclosing medical errors. Third, teaching error disclosure to senior medical students is practical, feasible and time efficient. Although every physician believes in the tenet of ‘first do no harm’, we acknowledge that error does occur. Thus, learning how to effectively communicate harm or potential harm to patients as a result of medical error is a critical skill that every physician must develop. The HEEAL framework provides a simple mnemonic that physicians can use for structuring communication and providing information to both patients and families as well as colleagues to maintain their autonomy.

Physicians face multiple barriers in disclosing a medical error including uncertainty, helplessness fear and anxiety [13,14]. While these barriers may impact a physician’s doubt about the utility of disclosure, we know that patients want open, honest communication from the physician concerning events that take place during care delivery [25–27]. Further, the healthcare institution must ensure that physicians have the skills needed to engage in the conversation and open the door to a dialogue that patients and families expect from their care providers when things go wrong [28]. The HEEAL intervention teaches specific skills that physicians may use in difficult communication encounters and provides strategies to help mitigate adverse reactions of patients and families. Addressing the situation forthrightly, using plain language without medical jargon, and offering an honest apology for how events transpired are highly desired by patients and families [25–27].

Additionally, arming physicians with a framework and etiquette for which to disclose and discuss bad news with their peers is a critically important and overlooked aspect in medical education. Given that likely most physicians find out about bad outcomes or circumstances around the management of a patient from other physician colleagues and that most physicians will deal with both having to disclose such information to a peer and have such information disclosed to themselves, learning this skill will likely lead to less secondary trauma to the physician(s) involved. These conversations are likely less stressful to have with colleagues than disclosing such information to patients and their families, yet it is still important given the current atmosphere of the workforce in the post-pandemic world. The utilization of this framework may ultimately contribute to improved wellness, critically needed in today’s workforce with record-high levels of burnout, workforce shortages, and numbers of physicians leaving practice [29–31]. The HEEAL framework provides an easy and accessible conceptual framework for which to structure and teach these conversations.

With regard to specific improvements in communication self-efficacy, knowledge and competence, we feel that students’ ability to report error within the healthcare system and take responsibility for the error, were likely due to a greater understanding of an enhanced culture of error reporting within institutions. In other words, safeguards were likely in place within institutions to support providers and designed to promote error reporting, creating a ‘just culture organization’, which was emphasized in the workshop [32]. Another improvement in communication self-efficacy was in providing information to patients regarding options for moving forward; for competence, assuring patients and families that an effort would be made to prevent similar errors from happening in the future. Actualizing these improvements in real-world clinical settings is tied to an enhanced culture of error reporting within institutions and it is acknowledged that further inroads are necessary to establish full error disclosure guidelines in all institutions and healthcare settings.

Items of least improvement in communication self-efficacy were the inability to express apology and remorse to the patient/family, and explain what would be done to help the patient recover. We believe the small effect seen in the later categories is largely due to the medical students’ relative lack of practical experience and limited exposure to the management of medical complications using second-line treatment strategies. Practical experience tells us that an apology is difficult in any situation. Enhancing the difficulty in this scenario is the students’ relative lack of personal experience with shouldering the responsibility for medical complications as well as less developed ethical reasoning skills that appear important in acknowledging errors [33]. Students may have had difficulty expressing true remorse to an SP, and while these scenarios are as realistic as possible, there is always an element of suspended disbelief on the part of the participants, especially when being asked to disclose a hypothetical error that one did not personally commit. We also believe that the limited exposure of students witnessing an apology on the part of senior medical personnel contributes to the difficulty in performing this behaviour de novo . Although we provided examples and role-play experiences for the students, they still have limited exposure to professional models for this behaviour, and thus, they struggle with managing such a complicated communication encounter [34]. With regard to students’ inability to explain what would be done to help the patient recover, this is again due to a relative lack of experience, particularly the potential utilization of resources such as social work, physical therapy, occupational therapy, chaplain services, financial counselling and community resources generally available to assist patients and families.

With regard to items that exhibited the least improvement in competence – students’ inability to allow patients and families to express their emotions and students’ inability to express humility – we feel this is largely due to the medical students’ relative lack of practical experience, including feeling somewhat uncomfortable talking with an emotional patient and family, as well as providing empathy. Again, students have limited exposure to faculty performing emotionally laden communication and this lack of professional role modelling limits their capacity to draw from multiple models to formulate new behaviours. Although the simulated environment provides a realistic setting and rich milieu for the development of this type of behaviour, it likely represents a very new experience for most students.

We have demonstrated that the HEEAL workshop is a beneficial addition to current medical school curricula in teaching error disclosure communication. It can be taught in a time-efficient, low-cost manner in the classroom and clinical skills laboratory. It is particularly appropriate to teach medical students these skills as this provides an exemplar of professional behaviour that can be reinforced on the wards and throughout their clinical training. The use of SPs provides students with an opportunity to simulate the tough conversation of error disclosure with a trained professional and develop communication self-efficacy in this area as well as receive formative feedback. SP encounters also provide educators and students with information regarding student competence levels.

Limitations to our study include that our training was limited to medical students at one institution. A more comprehensive cohort would include resident physicians, fellows, attending physicians and other providers who might have to disclose errors. Furthermore, our confidence and multiple-choice questionnaires were internally piloted but not validated instruments. Additionally, our number of participants was a small convenience sample of available volunteer students. As a result of this, we did not perform a sample size power analysis. These several limitations limit our ability to make generalizable commentary on the potential benefit to a larger and more diverse cohort of students.

This pilot data suggests that the HEEAL intervention provides an effective and efficient way for medical educators to teach senior medical students how to provide competent error disclosure to both patients and peers. The standardized patient methodology provides educators with a mechanism to assess learner competence in the acquisition of this important skill. Further study is required with larger cohorts and different learner types, for example, residents and attending physicians, to determine the generalizability of these results.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.