Simulation in healthcare education enables learners to practice in a realistic and controlled environment without putting real patients at risk. Deception can be incorporated to generate a realistic learning experience. We aim to perform a systematic review of the literature to study the effect of deception in SBE in healthcare.

Online database search was performed from conception up to the date of search (December 2023). Qualitative descriptive analysis included all published and unpublished works as for the quantitative analysis, only randomized clinical trials with an objective measurement tool relating to learner’s performance were included. Forward citation tracking using SCOPUS to identify further eligible studies or reports was also applied.

Twelve out of 9840 articles met the predefined inclusion criteria. Two randomized controlled trials were identified using deception for the intervention group and ten articles provided current knowledge about the use of deception in simulation-based education in healthcare. The aspects discussed in the latter articles related to the possible forms of deception, its benefits and risks, why and how to use deception appropriately, and the ethics related to deception.

Although this meta-analysis shows that using deception in SBE in healthcare by challenging authority negatively affects the trainees’ performance on the mAIS scale, this approach and other forms of deception in SBE, when used appropriately and with good intent, are generally accepted as a valuable approach to challenge learners and increase the level realism of SBE situations. Further randomized trials are needed to examine and confirm the effect of other deceptive methods and the true psychological effect of those interventions on validated scales.

Simulation is used in different aspects of healthcare education [1]. It allows graduates and professionals to put their knowledge into practice safely without harming an actual patient and to improve their skills through sustained, deliberate practice [2].

A genuine psychological and hands-on experience with realism generates appropriate assimilation of skills and allows the learners to transfer their learning into real clinical practice [1,3].

Deception has long been used in aviation, psychology and recently in healthcare education to generate a realistic learning experience with real-life features [1,3]. It causes someone to accept as true or valid what is false or invalid [4].

The potential advantages of using deception in simulation-based education (SBE) in healthcare must be balanced against the risk of psychological harm to participants and not damaging their trust in the educational team [3,5].

Several scoping reviews have examined this emerging subject, clarified key concepts and mapped future research [1,3,4,6]. However, no comprehensive review is available, and there is currently no clear evidence to indicate whether deception in healthcare education is beneficial.

Thus, we systematically reviewed the literature and studied the effect of deception in SBE in healthcare.

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [7].

The protocol was written before data extraction and included key information about the design and conduct of the systematic review (Appendix 1).

Due to the relative novelty of the subject, we included for the qualitative descriptive analysis all published and unpublished works regardless of article type, language or date of publication.

For the quantitative analysis, we included only randomized clinical trials. We based the search strategy on the PICO (population, interventions, comparisons and outcomes) model. The population was adult healthcare learners of any sex and specialty who underwent SBE using deception and were compared to other learners who did not experience deception. To be included, a trial had to use a defined outcome with an objective measurement tool relating to learners’ performance.

Because deception use in SBE in healthcare is an emerging field, we searched several resources to maximize the inclusion of all relevant studies. We searched Medline, PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, Cinahl and Mednar from conception up to the date of search (December 2023) and looked at the reference lists of included studies and previously published reviews. We undertook forward citation tracking using SCOPUS to identify further eligible studies or reports.

We built the search strategy with a medical librarian (AF) and conducted the search in Medline and applied it to other databases accordingly. Our systematic search strategy combined three concepts: deception, simulation-based training and the medical field (in a broad sense). We captured the ‘simulation training’ as a concept by including common analogous concepts such as ‘computer simulation’, ‘computer-assisted instruction’, ‘programmed instruction’, ‘simulated patient’, ‘standardized patient’ and consistent keywords with truncation such as interactive training, virtual or augmented reality, and computer modelling. For the ‘deception’ concept, we broadened the search terms to include ‘misconduct’, ‘false’, ‘deceiving’, ‘lie’, ‘trick’, ‘emotion’, ‘surprise’, ‘ethics’ and ‘cognition’. Finally, to focus our search on healthcare education, we combined topics of ‘internship and residency’, ‘clinical clerkship’, ‘medical education’, ‘nursing education’, ‘health occupations students’ and corresponding keywords. The detailed search strategy is provided in Appendix 2.

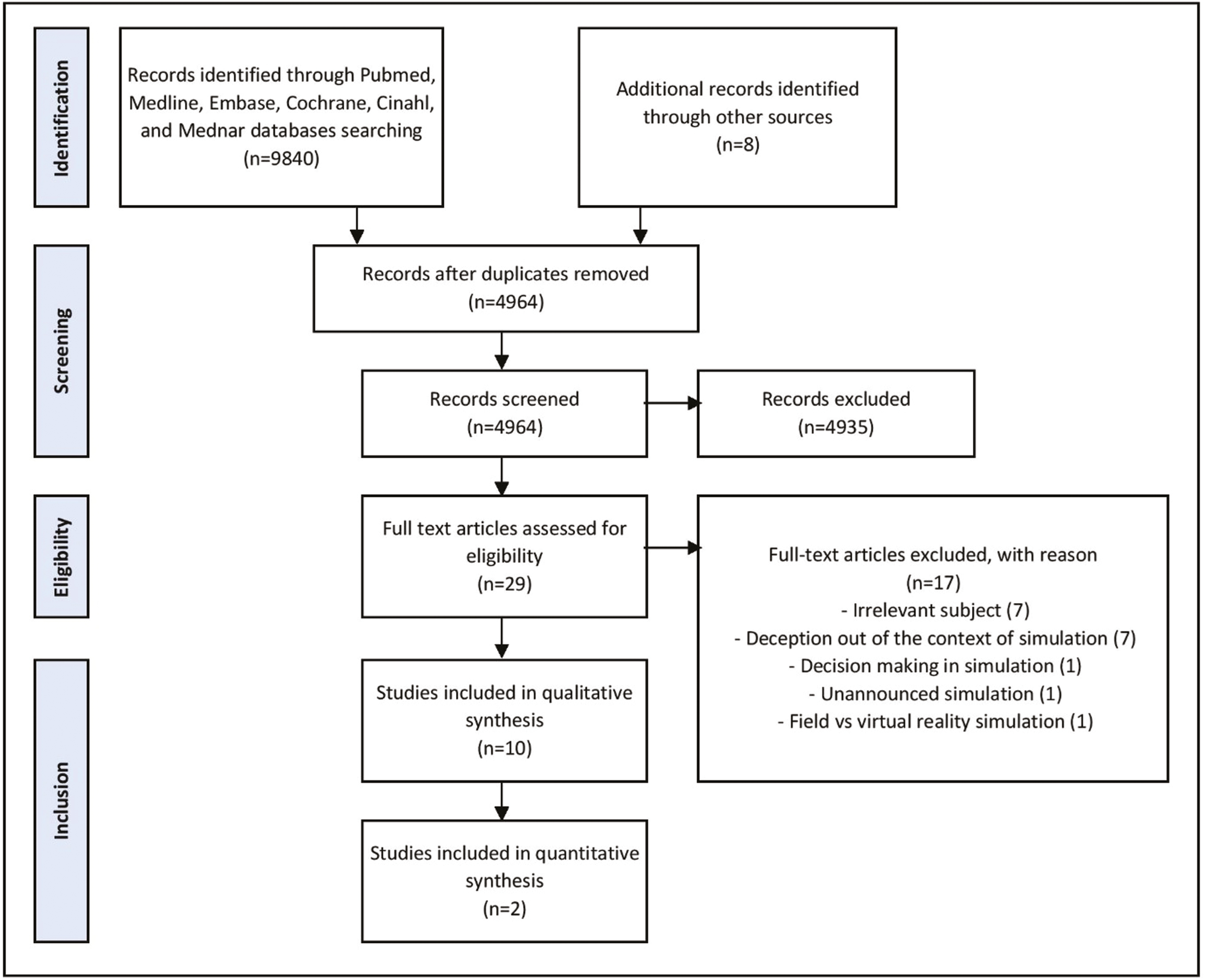

The database search identified 9840 articles in the literature. Reference list checking and hand search identified an additional eight articles that were imported to Zotero. After duplicate removal, two researchers (JS, AK) independently reviewed titles and abstracts of the remaining 4964 records and discussed inconsistencies until obtaining consensus. A total of 4935 were excluded after the initial screening. Next, they independently screened the remaining 29 full-text articles for inclusion. In case of disagreement, a consensus was reached by discussion. When necessary, a third researcher (NS) was consulted. A total of 17 texts were excluded for an irrelevant subject, discussion of deception out of the simulation context, discussion of other aspects of simulation or assessment of unannounced simulation patients. At the end, 12 articles were included, from which two were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and used for the quantitative analysis. The other articles were included in the qualitative analysis and consisted of five reviews (Table 3), one prospective study, one mixed methods study, one guideline text, one letter to the editor and one response to the latter. A PRISMA flow diagram was created to illustrate this process (Figure 1).

PRISMA diagram showing the detailed search strategy in relation to the effect of deception in simulation-based education in healthcare.

A data extraction sheet was developed and piloted on five randomly selected included articles and then refined. After finalizing the extraction sheet, one reviewer (AK) performed the initial data extraction for all included articles, and a second reviewer (JS) checked all proceedings. A third reviewer (NS) reviewed data extraction and resolved conflicts. We contacted study authors when the articles contained insufficient or unclear information.

Data were collected from the 12 included articles in tables. For each article, the following items were recorded when applicable: author, year, study type, study population and sample size, aspect of deception described, randomization process, procedure simulated, deceptive action and its variable, outcome and effect.

We evaluated the quality of evidence with the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI tool). It was developed and validated to measure the methodological quality of educational research studies. It is a six-domain score graded over 18 points, which evaluates study design, sampling, type of data, evaluation instruments, data analysis and outcome [8]. We assessed the risk of bias in the articles included using the Cochrane risk of bias (RoB) tool [9]. Two reviewers independently did both appraisals (AK, JS), and discordance was resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached.

Descriptive synthesis was used for the articles that were included in the qualitative analysis concerning benefits, risks, origin, success contributors, ethical issues, and determinants of deception in SBE in healthcare.

The two RCTs included in the quantitative analysis had similar designs. The outcome variable was the maximal modified Advocacy-Inquiry Scale (mAIS): a score that measures individuals’ response strength when challenging authority. It is a 6-point ordinal scale ranging from 1 (say nothing), the lowest response, to 6 (attempts to take over the case or other decisive action), the highest. This modified scale (Appendix 3) was validated in previous studies [10,11]. Multiple observations for the same outcome (repeated measurements) were conducted, and the maximal value was assigned for each learner as outcome measurement to allow the capture of any minimal benefit in terms of AIS modification. All participants had the same number of repetitive measures; thus, we did not find any risk in outcome measurement from this strategy. Measurements were made on the same scale across the included studies.

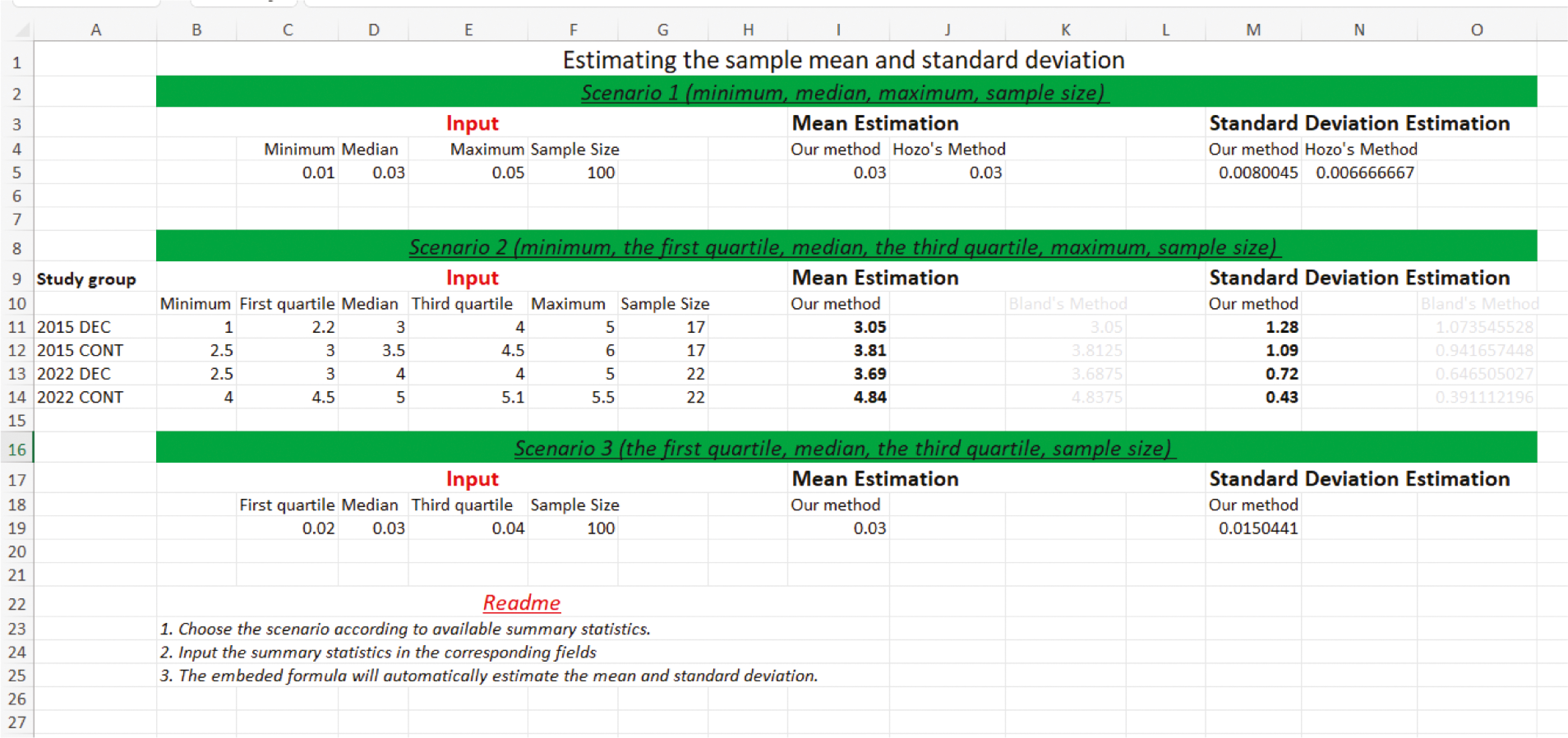

We used the mean difference (MD), a standard statistic that measures the absolute difference between the mean value in two groups. We searched each group for the mean value of the outcome measurement, standard deviation (SD), and the number of participants to perform the meta-analysis for continuous data using the MD. However, the authors of the two RCTs reported only medians, interquartile ranges (IQRs) and ranges (Table 1).

| Intervention | Control | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Median | IQR | Min | Max | N | Median | IQR | Min | Max | N | CI 95% | P |

| Friedman, 2015 | 3.0 | 2.2–4.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 17 | 3.5 | 3.0–4.5 | 2.6 | 6.0 | 17 | 0.06 | |

| Friedman, 2022 | 4.0 | 3.0–4.0 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 22 | 5.0 | 4.5–5.1 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 22 | 0.7–1.4 | <0.001 |

IQR: interquartile range; CI: confidence interval; mAIS: modified Advocacy-Inquiry Scale; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

We tried to contact the corresponding author of both articles without success. Consequently, we used Wan and colleagues’ approach to approximate SD and to impute a missing mean value from the sample size, the median, range and IQR of each group in the two studies [9,12] (Appendix 4).

Calculations for mean differences, confidence intervals and the quantitative analysis were conducted using RStudio 2021.09.0 + 351 ‘Ghost Orchid’ Release, and the ‘meta’ package (Appendix 5). Results are presented in Table 2.

| Intervention | Control | Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | MD | CI |

| Friedman, 2015 | 3.05 | 1.28 | 17 | 3.81 | 1.09 | 17 | −0.76 | [−1.56; 0.04] |

| Friedman, 2022 | 3.69 | 0.72 | 22 | 4.84 | 0.43 | 22 | −1.15 | [−1.50; −0.80] |

SD: standard deviation; MD: mean difference; CI: confidence interval; mAIS: modified Advocacy-Inquiry Scale.

We assessed and included a total of 12 studies in this review.

Ten studies provided current knowledge about the use of deception in SBE in healthcare. The key characteristics of those articles are provided in Table 3.

| Study | Type | n | Aspects of deception described |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alinier and Oriot, 2022 [1] | Review | NA | Definition Types Prevention of misunderstanding Effect Ethics Determinants Simulation fidelity elements |

| Calhoun et al., 2020 [12] | Guidelines | NA | Determinants Benefits High-risk situations Ethical considerations Application for educational practice Mitigation of negative effects |

| Calhoun et al., 2020 [4] | Mixed methods | 84 | Types Decision-making considerations Never events High-risk detriments Benefits |

| Calhoun et al., 2015 [3] | Review | NA | Elements of emotionally difficult simulations Core Relationships in emotionally difficult simulations Psychological safety Approaches Strategies for mitigation Opponents vs. proponents points of view |

| Goldberg et al., 2015 [13] | Letter to Editor | NA | Lacking grounding in empirical research Milgram experiments Framework to guide educators Elements of emotionally difficult simulation |

| Calhoun et al., 2015 [4] | Response to the previous letter to Editor | NA | Lack of supporting empirical research Milgram experiment Proposed framework Role of briefing |

| Truog and Meyer, 2013 [15] | Review | NA | Types Strategies for mitigation of its negative effect Milgram experiment |

| Gaba 2013 [16] | Review | NA | Death in simulation Challenging authority Milgram experiment Standards for application |

| Corvetto and Taekman, 2013 [2] | Review | NA | Simulated death: Advantages Concerns Recommendations |

| Gettman et al., 2008 [17] | Prospective (single arm) | 19 | Urology resident performance during an unexpected patient death scenario involving high-fidelity simulation Effect of deception on performance, usefulness, the realism of the scenario and feeling competent (Likert score) |

NA: not applicable.

Deception can be applied in two ways: by omitting information or other aspects of the environment (equipment, personnel) or by providing false information or faulty equipment [13,19]. Deception of learners results from a misunderstanding of the educational model due to insufficient preparation for the activity. It can also result from unexpected content during the activity, like altered equipment, unexpected action of a confederate or a deterioration of the patient’s condition. Furthermore, it may be caused by the absence of immediate consent between learners and educators (e.g. in situ unannounced simulation) [1].

The learners’ experience level is an essential determinant of the planning of the educational activity [18]. Thus, the level of complexity, fidelity and realism of the simulation activity has to be modulated based on the need, previous experience and learning outcomes of the targeted learners [1]. Content and face validity of the initial situation are essential concepts that can influence learners’ decision-making processes and interventions during SBE activities. A highly realistic situation could be helpful to get the highest performance from experts. Reliability is another crucial element in ensuring similar learning experiences between groups. Consistent use of a particular approach, technology, detailed scripting of key scenario elements and setup help the trainers to respond to the variability in learners’ decisions and actions. Additionally, the pre-determination of interventions from simulated participants and difficulty level is also as important.

A triangular model of simulation fidelity was presented by Kyaw Tun et al. It concerns the patient representation, the healthcare facilities and the clinical scenario, with an outer circle corresponding to the deception needed to increase the level of realism [23]. More recently, a different perspective was proposed to be applied to each simulation-based activity and includes four key elements: environmental, patient, semantical and phenomenal (Table 5). Each dimension can have its level of fidelity and can be supplemented by some level of deception to reach the intended level of realism and learning objectives [1].

Only two RCTs were conducted among second-year anaesthesia residents in the same institution and were eligible for the conduction of the meta-analysis. Overall, 78 learners were included and randomized using a computer-generated list on a 1-to-1 ratio to either intervention or control groups. Both studies approached deception through an authority-challenging situation during a difficult airway crisis but using a different variable (Table 4). Both RCTs evaluated learners’ performance using mAIS, and other non-objective secondary outcomes (feeling of learners during the activity). In both studies, the deceptive intervention aimed to make the learners challenge the authority (superior’s wrong decisions). While Friedman et al. in 2015 used the strict communication behaviour of a consultant anaesthetist as a deceptive intervention, Friedman et al. in 2022 used role-play as part of the study team to induce deception between learners. In the former, authors reported no significant effect of the consultant’s behaviour on trainees’ ability to challenge authority. In the latter, authors found that the intervention group demonstrated less-effective mean challenge scores and a lower number of individual challenges. In both studies, debriefing (during which the deception intervention was disclosed) followed the simulation-based activity. None of the learners felt upset from the interventions and everyone felt it was a helpful experience.

| Study | n | Population | Randomization | Procedure simulated | Deceptive action | Variable | Outcomes | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedman, 2015 [9] | 34 | Second-year anaesthesia trainee | Computer-generated list | Life-threatening airway crisis | Challenging the authority (consultant anaesthetist) | Superior’s interpersonal behaviour with trainees (strict vs. open communication dynamics) | Primary: - Maximal PS (mAIS) Secondary: - Feelings of the subject |

No |

| Friedman, 2022 [5] | 44 | Second-year anaesthesia trainee | Computer-generated list | Rapidly deteriorating difficult airway | Challenging the authority (consultant anaesthetist) | Superior’s role (subject in the study vs. acting a part in the scenario) | Primary: - Maximal PS (mAIS) Secondary: - Average mAIS by participant - number of challenges by participant - number of participants who made no challenges at all |

Yes |

PS: performance score; mAIS: modified Advocacy-Inquiry Scale.

| Dimensions of simulation | Elements | Examples of manipulations related to deception |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | Training venue Equipment Furniture |

• Specific positioning • Background noise • Intentional alteration |

| Patient | Full body simulator Organ simulator Physiological data |

• Technological limitation (e.g. absence of haptic feedback) • Disproportionate physical features • Alarm sounds of the monitor • Making a task more complicated than it is normally • Control of the simulator’s response |

| Semantical | Relation to clinical reality Embedded scenario participants Time modulation |

• Modification of the amount of information disclosed during briefing and debriefing • Evolving of the simulation based on the learner’s actions (rapid or slow evolution) • Absence of recovery despite appropriate actions • Intentional errors or behaviours (taking wrong actions/decisions, oppressive attitude) from embedded participants (clinician known or unknown to participants, simulated relatives, or one of the participants themselves) • Adjustment of patient deterioration of recovery depending on time and learners’ confidence level • Allowing the patient to die or not |

| Phenomenal | Participants’ level of engagement | • Not informing learners that they are taking part in an SBE activity (in situ simulation activity) |

SBE: simulation-based education.

The two RCTs included in the meta-analysis were scored using the MERSQI tool. It was developed and validated to measure the methodological quality of education research studies over six domains, with a maximal score of 18 [8]. A score of 12 or higher indicates high study quality [24]. The MERSQI scores of the two included RCTs (detailed in Table 6) are 14.5, indicating their high evidence quality.

| Study | Friedman et al., 2015 | Friedman et al., 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MERSQI item | Answer | Score | Answer | Score |

| Study design | RCT | 3 | RCT | 3 |

| Sampling: institutions | 1 institution | 0.5 | 1 institution | 0.5 |

| Sampling: response rate | ≥75% | 1.5 | ≥75% | 1.5 |

| Type of data | Objective | 3 | Objective | 3 |

| Validity evidence for evaluation instruments | Content Internal structure |

1 1 |

Content Internal structure |

1 1 |

| Data analysis: sophistication | Beyond descriptive analysis | 2 | Beyond descriptive analysis | 2 |

| Data analysis: appropriate | Data analysis appropriate for study design and type | 1 | Data analysis appropriate for study design and type | 1 |

| Outcome | Knowledge/skills | 1.5 | Knowledge/skills | 1.5 |

| Total | 14.5 | 14.5 | ||

MERSQI: Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

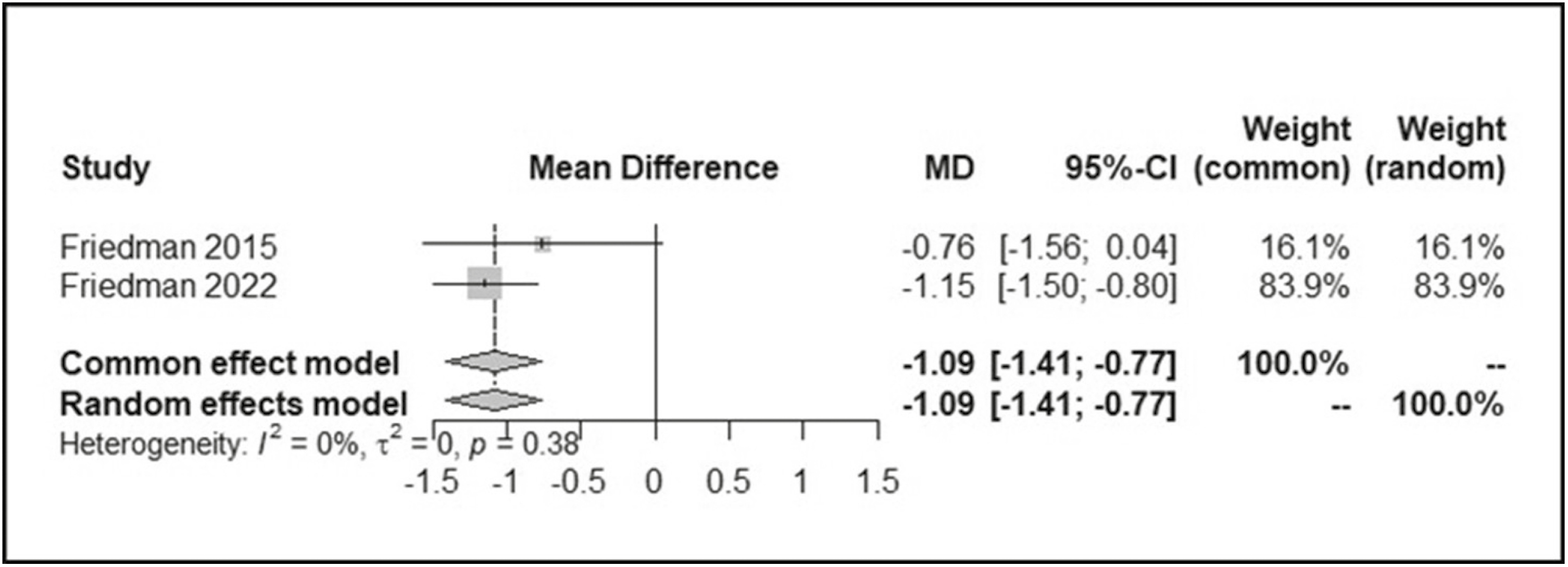

Both analyses of common and random effects of the studies included in the quantitative analysis show a negative effect of the use of deception on the performance of the trainee, which is statistically significant with a mean difference of −1.09 (CI [−1.41; −0.77]) in the intervention group. The estimates of the measures of heterogeneity (τ 2 = 0, I2 = 0%) and the test for heterogeneity (P -value = 0.38) indicate that there is no statistical heterogeneity between the studies (Figure 2).

Forest plot examining the effect of deception use in simulation-based education in healthcare.

Accordingly, as there is no evidence of heterogeneity, and as both fixed and random effects are similar and show strong evidence of an effect, we conclude that there is strong evidence that the use of deception negatively affects the performance of learners.

The risk of bias of the two RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane RoB tool (Table 7). Both studies had similar bias concerns regarding the randomization process, reporting of outcomes and missing data. Our assessment was based on the details provided in the texts and could not be completed with information from the authors due to a lack of response. For randomization, it was stated in both studies that the allocation sequence was random and completed using computer randomization. However, it was not clearly stated if it was concealed until participants were enrolled and assigned to interventions. In both studies, the authors did not display the baseline characteristics of the groups, so eventual baseline differences that could have affected the results could not be evaluated. During reporting of outcomes, multiple eligible measurements were done, and the highest was chosen, regardless of the value of the other measurements. This questions the representativity of the recorded outcome value and may lead to a biased estimation of the effect of the intervention. Consequently, the overall risks of bias in both studies indicate some concerns.

| Study | Bias arising from random sequence generation (selection bias) | Bias arising from allocation concealment (selection bias) | Bias arising from blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Bias arising from blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Bias arising from incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Bias arising from selective reporting (reporting bias) | Overall risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedman et al., 2022 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Friedman et al., 2015 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

The current meta-analysis shows that deception in SBE in healthcare negatively affects trainees’ performance. This subject is a novelty, and our systematic review and meta-analysis are the first to summarize the available evidence in the literature concerning this topic. Deception has long been a positive intervention essential for realism and better transference [6]. The observed effect in our analysis can be explained by the fact that students in the deception group experienced more challenging situations, making them perform worse than others who were not exposed to deception.

Deception is considered part of the art of simulation and valuable for learners’ development [1]. It creates complex situational and social realities of healthcare practice within the simulated environment [13] and allows realism with a high emotional and psychological authenticity. Consequently, it pushes learners to exercise critical thinking during the activity and develop adequate communication and relational skills to successfully navigate difficult interpersonal or hierarchical situations in the clinical environment [3].

Deception use in simulation has been linked to psychological harm at three levels: personal, relational and educational. Deception use can result in negative learner emotions (stress, anxiety, anger, shame) and a sense of self [13], which affect learning and memory [2]. It can result in mistrust and betrayal between the learners and educators, which can spill over into the clinical environment. Particularly, the failure to challenge the team leader could negatively affect the learner’s sense of self and make them experience self-reproach and shame for not challenging the simulated participant acting as a clinician [3]. Eventually, this may result in negative feelings about learning with simulation generally [2].

When learners’ psychological safety is ensured, deception is considered ethically appropriate since it has a worthwhile goal to improve the learners’ performances in future unexpected situations. It is a part of the fiction contract and the learner’s consent about SBE, placing them in a realistic situation [1]. Also, the possibility of psychological distress caused by a training session in learners is considered acceptable compared to the more significant distress that clinicians, patients and families live in actual adverse events. Ethical concerns associated with the deception use can be mitigated through careful briefing, debriefing and appropriate limits on the extent of the deception [3]. At the beginning of the activity, learners should only be briefed on what they need to know [19]. In the end, a non-offensive debriefing to analyse the situation with good judgment helps learners understand and accept the deceptive scenarios and prevents them from still feeling deceived after the simulation [1,22].

We found only 2 RCTs that the same lead author conducted, in the same institution, using the same deceptive action. Friedman et al. evaluated communication failures when there is status asymmetry or authority gradient between team members. They focused on challenging the hierarchical structure and speaking up against authority whenever learners believed the action or diagnosis was wrong [5,10]. Even though the studies were conducted at 7 years intervals and with different groups of students, it would be more rational to take the experience of different centres and various deceptive actions for a better estimation of the effect of the intervention.

The authors did not provide the complete baseline characteristics of the students included. However, it was clearly stated that they were second-year anaesthesia residents in both RCTs. Previous works have described the different intentions of learners depending on their experience level. Early learners focus on developing basic cognitive scaffolding skills [2] and do not yet possess the resilience to navigate the situation emotionally [12]. They give high significance to the learning outcomes, such as recognizing specific pathologies or practising a precise surgical procedure [1]. In contrast, more advanced learners, having already mastered the basics, use simulation to focus on nuances of care [2], and perform better when there is a higher level of realism [1]. In both RCTs, learners were junior clinicians hence can be considered as early learners. It was probably a very challenging scenario for them, which might have led to strong reactions and misunderstanding of what simulation is about, and affected their performance, as described in a previous article by Alinier and Oriot [1]. Although one of the goals of SBE in healthcare is to have learners understand and confront their limitations, the inability to challenge authority is not related to the knowledge base and skills but the learner’s character. Speaking up against authority can lead to delayed psychological harm, which cannot be detected directly at the end of the session [6]. Truog et al. suggested informing the learners clearly during the pre-session briefing that examining the hierarchical structure of authority is one of the learning goals. This way, they will still have the opportunity to learn strategies for speaking up to the authority without risking psychological harm or breaching of trust [6]. When the participants accept the challenge, the entire environment becomes ‘safe’ without lacking educational value via the avoidance of high-intensity events [14]. Coming back to our study, the briefing step was not clearly described in both RCTs and might have contributed to the failure of deception use if clear statements about challenging the authority were not made.

As a matter of fact, the briefing prior to the simulation activity consists of reviewing the session’s goals and objectives, establishing a fiction contract with learners, providing logistic details about the session and pledging to respect the learners. In fact, learners should believe the simulation model in all its components (physical, physiological, pharmacological processes) to make it work. It is part of the fiction contract to be established with learners to encourage them to suspend disbelief [21].

Technical elements of realism can be discussed in the briefing but do not need to be divulged technically to learners as it would not benefit their learning experience and bears no ethical issues [1]. Transparency and complete disclosure of the functioning of the simulation model (steps of the activity, interactions between team members) are essential parts of the pre-briefing part [18]. However, revealing the full content of the simulation activity may have limited educational value and might influence learners’ decisions and actions. Therefore, limited disclosure of the full content of a simulation activity and the situations that can impact team functioning reproduce more realistic situations [19]. Learners must accept the simulation model as an experimental learning modality and have a positive attitude towards it. The discussion of the objectives and the limitation of the simulation activity during pre-briefing promotes a positive learning experience and allows learners to achieve the educational objectives [1,20].

An acted role by an embedded participant caused the deception used in both RCTs. This is prone to trigger in the learners a feeling of anger against the authoritative person embodying hierarchy in the scenario. As a mitigation, the approach was disclosed during post-simulation debriefing or the analytical phase, as previously suggested [22], to maintain the trust of the educators and the faith in the educational technique adopted. Debriefing discussion with learners also helps manage their expectations regarding future similar real-life situations [1]. On the other hand, the subject who acted the deception intervention could have poorly acted so that he did not cause enough deception to stimulate action by the learners. Perhaps a more subjective deceptive tool (in the ‘patient’, monitor, environment) would have affected learners’ performance differently.

Both RCTs checked the learners’ feeling as a secondary outcome and stated that none of the learners felt bad about the experience. However, no objective measurement of the learners’ psychological state was made, which could be useful for future studies.

The strength of this study remains in that it is the first meta-analysis on the effect of deception use in SBE in healthcare. It gives a primary ground knowledge that can direct future changes in research in this field. Additionally, we did an extensive review that included grey literature to capture all publications related to the subject.

Our study had limitations. We could not reach the author of the articles for missing values. Although we used a validated approach to estimate means and SD, it remains an approximation that can differ from actual values. Nevertheless, we do not believe this risked the direction of the observed effect, but just the exactitude of the effect size. Additionally, the groups’ baseline characteristics (sex, age, ethnicity …) were missing. This could have given a clearer idea of the effect observed and the variables that could have played a role.

Deception is a fundamental part inherently existing in almost any SBE activities. It can be included in several forms and aspects by educators. It is considered as a double-edged sword, affecting negatively or positively the learning process. Its use should be finely tailored and adapted by educators according to the learners’ level of education and level of experience in SBE, in an oriented way during briefing and debriefing. Exploring simulation-specific outcome regarding the effects of debriefing on teams exposed to deception in future trials would also bring valuable data.

Although our meta-analysis showed that using deception in SBE in healthcare by challenging authority negatively affects the trainees’ performance on the mAIS scale, this approach and other forms of deception in SBE, when used appropriately and with good intent, are generally accepted as a valuable approach to challenge learners and increase the level realism of SBE situations. Further randomized trials are needed to examine and confirm the effect of these deceptive methods and the true psychological effect of those interventions on validated scales.

The authors would like to thank Ms. Aida Farha (AF), for her extensive help in the database research strategy.

J. Stephan and A. Kanbar are the co-primary authors of this article. They developed the search strategy, conducted the literature search and screened articles for inclusion. They performed the data extraction, the quality assessment, the statistical analysis and the interpretation of the data. N. Saleh and G. Alinier provided critical review and revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

No source of granting or financial support.

The data are available upon request from J. Stephan (Jeanclaude_stephan@hotmail.com) or A. Kanbar (Kanbar@outlook.com).

None declared.

None declared.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

The protocol was prepared before the start of the search by Dr. Anthony Kanbar and Dr. Jean Claude Stephan, in collaboration with Dr. Nadine Saleh and Dr. Guillaume Alinier.

To review systematically the effect of deception use in simulation-based education.

- Electronic Databases: MEDLINE using Ovid, PubMed, Cochrane, Cinahl, Mednar

- Manual search: by checking the bibliographies of relevant included studies

- Key authors will be contacted for clarification of study or access issues

- Search timeframe: from the inception of databases to December 2023

- Search strategy will be developed in collaboration with clinical librarian (AF) in Ovid and then applied to other databases accordingly

- Keyword and controlled vocabulary for three concepts:

◦ Deception: deception, misconduct, false, deceiving, lie, trick, emotion, surprise, ethic, cognition

◦ Simulation: computer-assisted instruction, programmed instructions, computer simulation, simulation training, simulation, interactive training learning teaching education instruction, virtual or augmented reality, model computer

◦ Medical: interns, residents, student, graduate, undergraduate, postgraduate, medicine, medical, nursing, nurse, training, education, health occupations, education, medical, education, nursing, clinical clerkship, internship, residency, delivery of Health Care, simulation patient, standardized patient

- Concepts were combined using Booleans AND, OR

- Studies published in English or French

- Evaluating the use of deception in simulation medical training

- All article types: randomized and non-randomized controlled trials, prospective studies, cohort studies, surveys, and retrospective and prospective case series, cross-sectional studies, reports, editorials, letters, commentaries, opinions

- Abstracts that clearly indicate that the study does not relate to the subject

- Non-medical simulation training

- Study authors

- Year of publication

- Study design and type

- Randomization procedure

- Setting

- Study population and sample size

- Aspects discussed

- Intervention

- Outcomes

- Effect

• The quality of the included studies will be assessed by at least two independent reviewers using standardized critical appraisal instruments

• Disagreements will be resolved by consensus or through discussion with a third reviewer

• We will provide a descriptive synthesis of the findings from the included studies structured around the benefits and disadvantages of the tool used

• We expected a low number of experimental studies. If included studies are sufficiently homogenous, we will meta-analyse their results in order to have a pooled rate of the tool used

None planned.

Computer-Assisted Instruction/ or programmed instructions as topic/ (14881)

2 exp Computer Simulation/ (286958)

3 exp Simulation Training/ (11412)

4 (simulation* or (interactive adj3 (training? or learning? or teaching? or education* or instruction*))).mp. (613760)

5 ((virtual or augmented) adj3 realit*).mp. (20105)

6 (model* adj3 computer*).mp. (17201)

7 exp Education, Medical, Undergraduate/ or exp Patient Simulation/ or simulated patient.mp. or exp Clinical Competence/ (129308)

8 standardized patient.mp. or “Internship and Residency”/ (60935)

9 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 (805374)

10 exp Deception/ (5584)

11 (decepti* or misconduct or mis-conduct or false).mp. (187533)

12 (deceiving or lie? or trick? or emotion* or surprise or ethic* or cognition).mp. (836467)

13 exp cognition/ or exp ethics, medical/ (240977)

14 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 (1071901)

15 (interns or residents).mp. (135793)

16 ((student? or graduate* or undergraduate* or postgraduate*) adj3 (medicine or medical or nursing or nurse?)).mp. (173404)

17 ((medical or nursing) adj3 (training or education*)).mp. (274997)

18 exp Students, Health Occupations/ (85102)

19 exp education, medical/ or exp education, nursing/ (269179)

20 clinical clerkship/ (5686)

21 Education, Medical/ or Patient Simulation/ or Education, Medical, Undergraduate/ or simulated patient.mp. (91589)

22 Students, Medical/ or Patient Simulation/ or standardized patient.mp. or “Internship and Residency”/ (102620)

23 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 (484196)

24 9 and 14 and 23 (9120)

Modified Advocacy-Inquiry Scale reproduced from Friedman et al., 2015 and Pian-Smith, 2009

| Type of reaction of learner | Score |

|---|---|

| Say nothing | 1 |

| Say something, obtuse | 2 |

| Advocate or inquire | 3 |

| Advocate or inquire repeatedly; with initiation of discussion | 4 |

| Use crisp advocacy-inquiry | 5 |

| Take over management of the case | 6 |

Wan and colleagues’ methodology to approximate standard deviation and to impute a missing mean value from the sample size, the median, range and interquartile range of each group in the two studies.

Excel file with calculator of the approximated values, provided in the article of Wan and colleagues, and available upon request.

install.packages(“meta”)

library(meta)

# Defining Data frame

tbl1 <-data.frame(study=c(‘Friedman 2015’,’Friedman 2022’),

year=c(‘2015’,’2022’),

n.dec=c(17,22),

mean.dec=c(3.05,3.69),

sd.dec=c(1.28,0.72),

n.con=c(17,22),

mean.con=c(3.81,4.84),

sd.con=c(1.09,0.43)

)

head(tbl1)

# Calculation of mean differences (MD) with CI

with(tbl1[1, ],

print(metacont(n.dec, mean.dec, sd.dec, n.con, mean.con, sd.con),

digits=2))

with(tbl1[2, ],

print(metacont(n.dec, mean.dec, sd.dec, n.con, mean.con, sd.con),

digits=2))

# Meta-analysis

res.dec = metacont(n.dec, mean.dec, sd.dec,

n.con, mean.con, sd.con,

comb.fixed = T, comb.random = T, studlab = study,

data = tbl1, sm = “MD”)

res.dec

# Forest plot

forest(res.dec, leftcols = c(‘studlab’))