Globally, practice education is a core component of physiotherapy training. Physiotherapy educators struggle to find sufficient workplace placements to ensure adequate clinical experience. Simulation-based learning (SBL) could complement clinical workplace experiences and bridge the gap between demand and provision. This study explores academic physiotherapy educators’ views and experiences of practice education and the potential contribution of SBL.

Representatives from all six Schools of Physiotherapy on the island of Ireland participated in focus groups. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Qualitative data were analysed using interpretive description methodology.

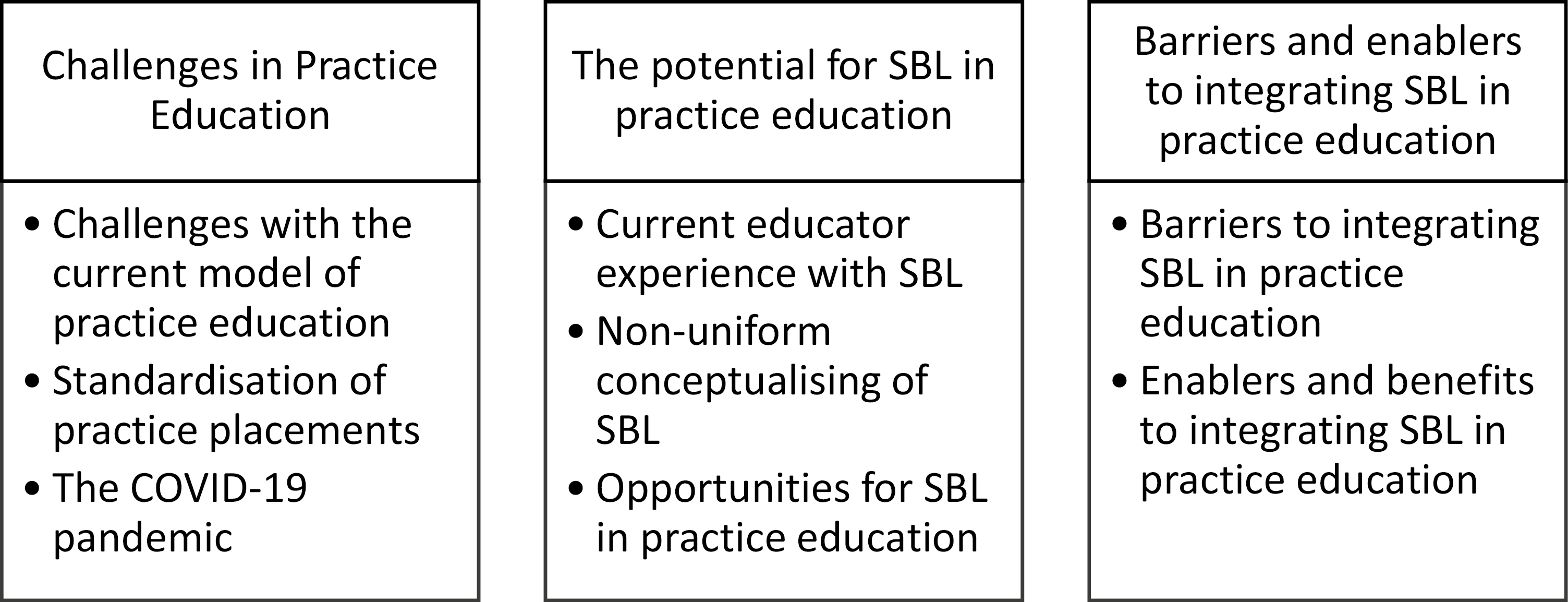

We conducted seven focus groups with 29 academic educators (26 females and 3 males). Three core themes were identified: (i) challenges in practice education, (ii) the potential for SBL in practice education and (iii) barriers and enablers to integrating SBL in practice education. COVID-19 had dual impacts, both exacerbating challenges and precipitating innovations in practice education. Analysis revealed guidance for how to fit SBL within practice education although varied understanding and limited experience with using SBL remained. Barriers to SBL included cost, time, logistics and stakeholder buy-in, while collaboration represented a key facilitator. Perceived benefits of SBL included enhanced student capacity and experience.

A number of contributing factors threaten traditional workplace-based physiotherapy practice education in Ireland. SBL may reduce this threat and solicit ever better performances from students. Future research should examine the feasibility of proposed SBL deployment and foster buy-in from key stakeholders.

What this study adds

• We have established, a number of contributing factors threaten traditional workplace-based physiotherapy practice education in Ireland including the 1:1 model of supervision, the growth of physiotherapy programmes, a reliance on the good relationships between the universities and clinical sites, the lack of physical space for students in the clinical environment.

• Simulation-based learning (SBL) has the potential to reduce the threat to physiotherapy practice education and solicit ever better performances from students. Through the strategic integration of into physiotherapy curricula: before placement to prepare students for the clinical environment, during placement to allow students deliberate and repeated practice of specific patient scenarios they have or will encounter and after placement to demonstrate learning among peers. SBL could also be used as a remediation strategy for students who are under performing.

• There are a number of barriers to the integration of SBL into physiotherapy curricula including a lack of uniform conceptualisation of SBL among physiotherapy educators. Other barriers including cost, training of staff, access to resources, logistics and consultation with other key stakeholders need to be considered before SBL can be integrated successfully into physiotherapy curricula.

Globally, educators struggle to meet the demand to find clinical sites to prepare physiotherapy students [1]. COVID-19 has exacerbated this situation. Practice education is a key component of physiotherapy education with World Physiotherapy (WP) stipulating that practice education must account for ‘no less than one-third of the curriculum’ [2]. Practice education is defined as the delivery, assessment and evaluation of learning experiences in practice settings, including institutional, industrial, occupational, primary healthcare and community settings [2]. Students must gain experience across a number of different clinical and professional behaviours, to enable them to develop the competence and autonomy to function as entry-level practitioners (Table 1). According to mandates by health regulators (Health and Social Care Professionals Regulator in the Republic of Ireland (CORU) and the Chartered Society of Physiotherapists (CSP)), physiotherapy students on the island of Ireland must complete 1000 hours of practice placement prior to graduation [3,4]. Thus, physiotherapy educators must provide opportunities for learning as outlined by the WP to integrate knowledge and skills and be provided with opportunities to enhance their clinical skills in Assessment, Examination, Evaluation, Diagnosis, Planning, Treatment/intervention, Re-evaluation, Communication skills, Professional behaviours and Interprofessional socialization. In recent years, the growing number of physiotherapy programmes in Ireland has increased pressure on universities to secure practice placements for their physiotherapy students [5].

| Topic | Questions |

|---|---|

| Topic One: Current status of clinical education | -What are the current challenges with regard to clinical placement? |

| Topic Two: Experience of simulation-based learning | -What experience do you have, if any, using simulation-based learning? -How have you used it routinely as part of your teaching? |

| Topic Three: Barriers/challenges to developing and implementing a programme for simulation-based clinical education | -What challenges have you encountered or do you foresee for using simulation-based learning for clinical placement? -What are the potential strategies/resources needed to overcome these challenges? |

| Topic Four: Benefits of simulation-based learning | -What do you foresee as the benefits of utilizing simulation-based learning? -What ideas do you have to enable your students to benefit more fully from simulation-based learning? |

Simulation-based learning (SBL) represents an untapped practical solution to increase capacity in Irish physiotherapy practice education [6]. SBL in physiotherapy education is used extensively in Australia [1,6–14]. Similar to our colleagues in Canada [15], the potential role for SBL as part of practice education in Ireland is underexplored and poorly understood. This study explores Irish academic physiotherapy educators’ views and experiences of practice placement and SBL.

We used a qualitative interpretive description (ID) methodology [16]. ID methodology applies to qualitative inquiry across health professions when a study aims to capture the subjective experience of a population and intends to use this knowledge to inform practice [17]. In line with ID methodology, we used participants’ subjective experiences with two main aims: (a) to support continuous quality improvement of practice education, and (b) to help educators design an effective educational SBL experience [17]. Educators from all six Physiotherapy Schools on the island of Ireland were invited to participate in focus groups. Educators in this instance refer to those who are employed in a School of Physiotherapy and are involved in teaching physiotherapy students. An invitation letter, participant information leaflet and consent were sent to all the Heads of Physiotherapy Schools in Ireland. The Head of School then distributed this to their staff and those interested in participating contacted one of the joint first authors. In the case of the host institution, the joint first author who is not a member of the RCSI School of Physiotherapy contacted the physiotherapy educators directly to invite them to participate.

The authors have expertise in health professions educational research, physiotherapy education, simulation and health economics. One of the joint first authors is an academic physiotherapy educator and another author is the Head of the School of Physiotherapy; neither are directly involved in practice education. Three of the authors are members of the RCSI SIM Centre for Simulation Education and Research. Two authors are experienced simulation educators with one author having significant expertise in qualitative research. To ensure an external perspective and to provide a distinct lens, one author is a qualitative researcher with a background in health economics.

All focus groups were conducted via video conferencing technology (Microsoft Teams (Microsoft United State of America)) and audio-recorded. A topic guide was developed and piloted in two focus groups conducted with the joint first authors’ institutional physiotherapy educators. These focus groups were facilitated by two researchers from outside the School of Physiotherapy; neither was involved in the supervision of the relevant staff. Based on the pilot, two questions were removed from the topic guide and included in the data collection form instead. Remaining focus groups with educators from the other five Schools of Physiotherapy were conducted using the amended topic guide (see Table 1).

Demographic data were collected, including: gender; years of experience in higher education as a physiotherapy educator; areas of expertise and details of clinical education activities used that do not involve direct patient contact. Details on the structure of practice education at each School of Physiotherapy were also collected, i.e. duration of each placement and number of placements.

All participant data were pseudo-anonymized for analysis. Prior to analysis, the transcripts were made available to the participants for review and clarification. The analysis had four phases. In the first phase, three authors familiarized themselves in the data by listening to the audio recordings, checking the transcriptions for accuracy and reading the notes from the focus groups. These authors then coded line-by-line, using constant comparative analysis of the interviews to create initial focused codes. The transcripts were coded independently. Two authors used Microsoft Word and Excel and one author coded the transcripts using NVIVO (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018, Version 12). The authors then met and achieved consensus about codes through discussion. In the third phase, four authors met to elevate and combine key concepts and to identify major themes. In the final phase, the four authors met to examine the relationships between major themes to examine how they related to each other and to accurately represent the participants’ views and experiences of practice placement and SBL.

Quantitative data were entered into Microsoft Excel 2016 and analysed using descriptive statistics.

We completed seven focus groups involving 29 educators from all six Schools of Physiotherapy in Ireland. Focus group participation ranged between 2 and 6 participants and the duration ranged from 31 to 74 minutes. See Table 2 for an overview of participant characteristics. Of the 29 participants, 11 were involved full- or part-time in a practice education capacity, securing and allocating practice placements for physiotherapy students.

| Gender | 3 males; 26 females |

| Median (range) years of experience in higher education | 8 (1–22) |

| Expertise according to clinical area (n =) | |

| Practice education | 11 |

| Research methods | 10 |

| Musculoskeletal | 9 |

| Respiratory | 7 |

| Neurology | 6 |

| Health promotion | 1 |

| Rehabilitation | 1 |

| Care of elderly | 1 |

| Health promotion | 1 |

Participants reported leading clinical education activities that did not involve direct patient contact. These included case studies, reflective diaries, role-play and case presentations. Participants also described problem-based learning, patients as educators, interprofessional learning, reflection on videos, telehealth courses, Making Every Contact Count training [18] and training provided by the national health service.

Based on our analysis, we identified three core themes: (1) challenges in practice education, (2) the potential for SBL in practice education and (3) barriers and enablers to integrating SBL in practice education (Figure 1). We now describe these three major themes and their subthemes and include representative quotations, e.g. P01F, FG1 is participant 1 (female) from focus group 1.

Themes and subthemes identified from analysis of focus groups to explore physiotherapy academic educators’ views and experience of simulation-based learning (SBL).

Participants indicated that the 1:1 model of student allocation with practice educators was a ‘potential limitation’ (P12M, FG4) and that perhaps a 2:1 model of supervision could ‘lead to service productivity’ (P12M, FG4). This long-standing 1:1 model of supervision in practice education has not been adapted to match the increasing number of students in Ireland in recent years with one programme reported increasing, ‘from 60 to 90 [students]’ (P26F, FG7). Participants lamented ‘that for a long time, capacity is an issue’ (P08F, FG3). This issue led to ‘competition constantly’ (P02F, FG1) between universities to place students. On the one hand, universities ‘rely so heavily on those good working relationships with our clinical colleagues’ (P25F, FG7) and on the other hand, educators were aware that students ‘can be perceived by the clinicians on the ground as being a burden’ (P03F, FG2):

[The clinical departments are] “very tiny environments,” and “the students don’t have somewhere to go to do their work. They’re then sitting on a desk that’s to be used for a very particular member of staff to actually write notes.” (P05F, FG2)

Participants highlighted the challenge in ensuring that students get opportunities to refine all competencies and skills on practice placement.

My main difficulty on placement… is… students having the opportunity to get certain skills, particularly around critical care [and] more complex cases that can sometimes be challenging. (P21F, FG5)

This lack of standardization threatens placements ‘meet[ing] CORU registration’ (P16, FG5) due to the unavoidable variability in real-world practice education, which however impacts students’ learning and development, for example the variability in patient presentations that are appropriate for the student learning needs.

…you’re really dependent on who’s there…and available….so, it’s not necessarily specific enough to each student in terms of their own personal development in clinical reasoning skills. (P20F, FG5)

This ‘lack of control’ (P07F, FG2) by universities over what students experience on practice placement may contribute to the ‘the hidden curriculum from a professionalism point [of view]… [due to insufficient] standardization..’ (P07F, FG2).

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted practice placements, with universities having to ‘cancel placements’ (P22F, FG6) due to ‘social distancing, staff redeployments, staff being unwell’ (P19F, FG5). Even when students were on placement, services were suspended and reduced student ‘opportunities or access to suitable patients’ (P15F, FG4). To compensate for disrupted student experiences while on practice placement, educators lamented that they ‘had to go to pass/fail’ (P26F, FG7), which created ‘a lot of anxiety from the students about how this is going to be reflected in their final classification’ (P26F, FG7). However, COVID-19 also presented ‘positives as well as negatives’ (P09F, FG3), promoting innovation through the use of telehealth. One university ‘replaced [a full placement] completely by simulated placement’ (P04F, FG2). Greater flexibility with expected onsite presenteeism allowed students to engage in other valuable learning activities.

Some students, maybe start later in the day or finish earlier and are onsite for less time, but are supported through this digital Learning Academy offsite using things like reflective practice and in some cases, scenarios, but also service delivery projects. (P08F, FG3)

Participants described having varying levels of experience with SBL, ranging from ‘absolutely none’ (P10F, FG3) or ‘very limited experience’ (P02F, FG1) to being able to ‘mock up scenarios of patients having a particular diagnosis or a particular set of symptoms, and mimic that as best we can in the practical classroom setting, and then enabling students to try and problem solve how they would manage that situation’ (P28F, FG7). Some educators created more structured simulated activities, describing opportunities ‘to explore … high-fidelity simulation, and have access to the computer system to be able to observe what’s going on in the room, manipulate settings, and... to use a room to debrief in’ (P28F, FG7). Participants from one university reported developing and delivering a full week of simulated activities across four specialities of physiotherapy ‘musculoskeletal, respiratory, neurology and care of the elderly’ (P02F, FG1).

Given the varied exposure to SBL, the majority of participants did not have a common language or shared understanding about SBL. Some participants referred to ‘the technology that’s available’ (P26F, FG7) or expressed concerns over being able to ‘move manikins around’ (P17F, FG5), indicating their perception that SBL only involved immersive manikin-based simulation, referred to some as high-fidelity simulation. However, some participants acknowledged ‘a lack of knowledge and an ignorance’ (P26F, FG7), with SBL being viewed ‘as an adjunct’ (P26F, FG7) to practice education. However, those who had more extensive experience of SBL reported observing a lack of understanding of SBL among clinical colleagues.

There is the definite lack of understanding … about what simulation is and what it can do. So, we now have a bit better understanding because we actually did [it] for a week. But when it comes to managers, tutors or other clinicians, they don’t know... even when we tell them, “Our students were out on sim for a week.” They don’t know what that is, they don’t know to what extent, they don’t know the quality…. And I had a conversation with another tutor… and she kept saying, “Oh, this is the student’s first placement.”…. And I said, “Well, actually they did have a week in sim.” …. I started describing what they had done, and she had a complete change in attitude then. (P02F, FG1)

Despite varied levels of experience and different conceptualizations of SBL, most participants expressed enthusiasm for further integration of SBL at varying stages in the practice education pathway. This included recommendations for its integration before, during and after placement. Moreover, SBL could be applied in ‘earlier’ (P16F, FG5) stages of the programme. The opportunity for students ‘to build confidence in their skills, in their clinical reasoning’ (P20F, FG5) or to have ‘covered certain competencies’ (P20F, FG5) in advance of their clinical placement was a widely shared view. Repetition and remediation opportunities during placement represented affordances for a ‘student that’s struggling’ (P16F, FG5) or for those needing to ‘rehearse again how you might treat the patient’ (P28F, FG7). SBL potentially fostered peer learning opportunities since SBL could prompt students to share their practice placement experience with others at the end of a placement.

And I could see that it would be lovely at the end a big block of placement, so that they…share their experiences. [Typically] they finish up on placement wherever they are in the country, they go off for their holidays and come back in January… there’s no real tying up of that big semester where they were out…So I think it will be lovely to tie up the end of a placement, maybe. I think it could stimulate nice deep conversations with them in small groups as well. (P16F, FG5)

Participants identified obstacles to integrating SBL in physiotherapy practice education of which ‘funding would be the main barrier’ (P10F, FG3) as well as costs associated with ‘travel’, ‘tutors’ time and pay for the simulated patients’ (P02F, FG1). A ‘national fund’ (P19F, FG5) for simulation was mentioned but access and priority to this funding were seen as a barrier as it was felt that physiotherapists are ‘generally down in the pecking order for where funds go unfortunately’ (P19F, FG5). Additional challenges included the development of realistic scenarios that allowed students to develop competency, which ‘would take a little bit of working through’ (P21F, FG5) and the ‘training and teaching of the staff’ (P21F, FG5). There were also concerns about ‘logistics’ (P02F, FG1) and access to resources since ‘the lab is in constant demand and we can’t just have it when we want it’ (P01F, FG1).

Participants also highlighted ‘gaining student buy-in’ (P26F, FG7) as a potential challenge. Buy-in from other stakeholders such as the regulatory body was viewed as important and potential challenge, with questions about ‘whether CORU would have an issue’ or ‘…the acceptance of that on clinical sites’ (P08F, FG3). Some participants expressed concern regarding the ‘authenticity of it [simulation] for students’ (P23F, FG6) and some indicated a preference for traditional placement ‘If I have an ideal situation, would I take simulation, or would I take a real placement? I’d probably take a real placement’ (P16F, FG5).

In terms of the vital role of collaboration in promoting SBL, participants reported enthusiasm ‘for universities to work together as well and maybe the university hospitals’ (P09F, FG3) as there was no need ‘to reinvent the wheel’ (P09F, FG3) with regard to developing resources for SBL. There was even a consideration for the potential for ‘global collaboration’ (P26F, FG7) to promote sharing of educational resources.

In terms of benefits of integrating SBL in physiotherapy practice education, participants felt that SBL could enhance the students’ experience, viewing it as ‘a lovely bridge to clinical’ (P20F, FG5) as it allows students to practice in a safe environment with no risk to a patient.

Students can make mistakes, they can make errors in their communication, they can miss things, and they have the opportunity to learn from that and no harm has been done. (P03F, FG2)

…it just gives them [students] an opportunity to carry out something in a safe environment and get some feedback and hone their skills before they’re actually allowed or able to go through with a patient. So, I think a lot of it would be the benefit in terms of that, the, environment. (P23F, FG6)

Communication between educators in academic and clinical settings could be problematic at times. SBL provided a platform for all educators to work together and in the instance of a 1-week simulated placement:

… it was a really great opportunity working and designing the educational sessions with each of the clinical educators… we couldn’t get our students out to University Hospital, but we brought the educator from the University Hospital to them in the sim. And that was a really nice opportunity for the students to feel a more authentic experience and for the educator to really make sure that the session was tuned to what they were likely to see [in terms of] proforma documentation from their hospital. (P04F, FG2)

According to our participants, SBL in physiotherapy practice education had the potential benefit of enhancing practice education capacity: ‘Maybe having that level of simulation completed before they go, can give that confidence to [clinical] educators’ (P20F, FG5) and also ‘take the pressure off the [clinical] educators’ (P25F, FG7). Standardized SBL could also ensure that students met all competencies before graduation and compensate for variation in students’ exposure on practice placement.

…if you do a respiratory placement in the middle of summer, you might not get the same experience as somebody who does a respiratory placement in winter so, from a respiratory point of view, to give the students the opportunity to engage in those kinds of scenarios that they might’ve missed on clinical placement. I think it’s nice to have that option there for those students to make sure that they’ve covered that before they graduate. (P21F, FG5)

We explored academic physiotherapy educators’ views and experiences of practice placement and SBL. Based on our results, physiotherapy practice education in Ireland faces complex challenges which the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated by reducing clinical capacity. Educators were interested in developing SBL physiotherapy education to support practice education in Ireland. However, our findings also highlight some practical considerations in the Irish context.

For years, the physiotherapy practice education community in Ireland has faced pressure to meet the current stipulation of a 1000 hours of practice placement [5]. Participants in our study highlighted several contributing factors to this pressure, including: (a) increased growth of physiotherapy programmes; (b) the current 1:1 model of student:clinical educator; (c) a perception that students are seen as a burden in the clinical environment; (d) an overreliance on the goodwill of clinicians; and (e) a general lack of standardization across practice placements. Previous literature has reported that clinical educators find delivering practice education burdensome and stressful [19] as they struggle to provide clinical service provision while meeting students’ needs [20]. A 2:1 model of practice education can alleviate the perceived burden of students on clinical educators [21]. While physiotherapy students in Ireland have expressed a preference for a 2:1 model in their earlier clinical placements, a 1:1 model is preferred later in placements to demonstrate clinical independence [5]. The lack of standardization of practice placements leads to inconsistencies in grading observed by students across sites, which students worry has detrimental effects on their final degree classification [22].

While COVID-19 exacerbated capacity issues within practice education [23], it also resulted in innovation. At the outset of the pandemic, the regulator in the Republic of Ireland, CORU, acknowledged that educators were best placed to implement contingency plans to address the practice requirements of their students [24]. Educators embraced this guidance, allowing students to work flexible hours, work from home through the use of telehealth and in one case SBL was used to achieve the learning outcomes of the missed practice placement. In addition to more standardized student experiences, which cannot be guaranteed in traditional clinical placement [8], SBL addresses issues with capacity [8] as demonstrated by a randomized controlled trial in which reported part education in the simulation satisfied clinical competency requirements comparable with the clinical immersion. SBL also provides a platform for peer observation [25]; where the use of observer tools to facilitate active learning and incorporating observers views in the debriefing can promote attainment of learning outcomes for observers in SBL. SBL therefore has the potential to provide a practical solution to address the very real and perceived issues related practice placement.

In the health education literature, SBL has been deployed in a number of different ways. Participants in our study described different models for SBL within physiotherapy practice education in Ireland. Firstly, SBL could be used to prepare students before placements. This model has been tested whereby one group of students had the first week of a 5-week clinical placement replaced with SBL and the other group completed 5 weeks in the clinical setting [7]. The SBL in this study incorporated encounters with standardized patients and other structured learning activities including peer learning, feedback sessions and opportunities for self-reflection. Both quantitative outcomes relating to clinical competence and confidence and qualitative data were collected. There were no differences in clinical competence and confidence between the groups at the end of the 5-week placement and the students positively reflected on the timing of the SBL week. SBL has been used successfully as a remediation strategy in nursing and medicine [26,27] and could therefore be considered during placement for physiotherapy students not meeting required standards of proficiency. However, remediation is generally underreported [28,29] and to the best of our knowledge has not been widely used in physiotherapy. Further suggestions included using SBL to allow students to gain competencies they did not have the opportunity to develop while in the clinical environment. This aligns with SBL applications by the Australian Physiotherapy Board, which allow physiotherapists seeking registration in Australia to attain all the necessary competencies through SBL [30]. Further, SBL could follow practice placements to consolidate skills via peer learning, which leverages a key aspect of SBL to re-enforce learning and develop competence through repetitive practice [31–32]. Despite the evidence that supports SBL [33] and its routine use in healthcare education globally [34–36], a number of participants expressed hesitancy about the appropriateness of SBL to form part of practice placement hours. This hesitancy may, in part, reflect the limited exposure of participants to SBL as well as a lack of shared understanding about this educational process. This lack of shared understanding of SBL has previously been reported in Canadian physiotherapy educators [15].

Despite this hesitancy, participants generally agreed that SBL could increase practice education capacity. This is particularly important in the Irish setting given our documented under supply of physiotherapists which is 30% lower than the EU-28 average [37]. This statistic, coupled with our ageing population [38], and the rehabilitation of COVID-19 survivors [39], demonstrates an urgent need to depart from the status quo of practice education to train more physiotherapists. SBL has the potential to increase capacity; however, the development and implementation of an SBL programme for physiotherapy education are expensive and logistically challenging. Additional work is required to explore the cost and value of simulation [40,41]. Geographically, Ireland is a small country which provides unique opportunities for sharing resources and collaboration. Collaboration between physiotherapy schools in Australia was observed in a Health Workforce Australia-funded project [42]. We would advocate setting up a community of practice to support this in Ireland. SBL costs can also be reduced through the use of students as simulated patients, which has been demonstrated to enhance peer communication and patient empathy; however, there is significant heterogeneity in terms of outcome measures used and the training provided for peer patients [43]. Participants in the current study highlighted stakeholder buy-in as a key consideration. Key stakeholders identified included students, clinical educators and the regulatory bodies responsible for accrediting physiotherapy programmes (CORU and CSP). The involvement of stakeholders in the development of SBL for practice education will promote curriculum developers to make better-informed decisions as well as empowering stakeholders [44,45]. Current research has demonstrated that students positively perceive SBL [46]. Future research should engage clinical educators who provide up to one-third of the academic content of university programmes through practice education [2]. Ultimately, regulators must endorse any change in approach to practice education and will also need to be consulted in the development of SBL for physiotherapy practice education.

This research addresses a number of topical issues within practice education in Ireland including capacity, COVID-19 and the current models of practice education. Uniquely, the island of Ireland and its physiotherapy schools are divided into two separate jurisdictions: those in the Republic of Ireland are regulated by CORU; and the one physiotherapy school in Northern Ireland is regulated by CSP. Despite these separate governing bodies, practice education faces uniform issues. Our study included every institution on the island with strong representation from practice education coordinators who have lived experiences of current challenges with practice education. The participants had limited experience and exposure to SBL and lacked shared understanding of the scope of SBL, which to some extent limited the discussion around its potential use in physiotherapy practice education. SBL is not routinely used in physiotherapy education in Ireland and there are a broad range of practices within SBL, both of which potentially contributed to this non-uniform understanding.

Physiotherapy practice education in Ireland confronts immense pressure due to a number of contributing factors. This pressure will only increase as the requirement for additional physiotherapists in the health service grows. SBL has the potential to reduce this pressure, solicit ever better performances from our students and enhance their learning. A number of different models of SBL deployment were proposed by participants in the current study, which would require additional resources and collaboration between the Schools of Physiotherapy on the island of Ireland. Future research should test the feasibility of these models and gain buy-in from key stakeholders including students, regulatory bodies and educators.

The authors wish to thank the participants for their time in participating in this research study.

OOS and CM designed the research study. OOS, CM, SMcD and CC contributed to the ethics submission. OOS and CM coordinated participant recruitment and OOS, CM and CC coordinated data collection. OOS, CM, JL and WE contributed to data analysis. OOS, CM and WE wrote the manuscript with contributions from CC, SMcD and JL. All authors contributed to manuscript revisions and read and approved the submitted version.

The work presented in this manuscript was supported by the Irish Research Council, New Foundations funding scheme.

The data sets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data sharing and ethics permissions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical approval was obtained from RCSI Research Ethics Committee. Record ID: 212540459

Not applicable.

RCSI SIM is a CAE Healthcare Centre of Excellence and receives unrestricted funding from CAE Healthcare to support its educational and research activities.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.