This scoping review aims to examine and map the current state of faculty development for healthcare simulation educators. This review will include an exploration of the range and type of faculty development programs designed to enhance simulation-based education (SBE).

Simulation has become a staple method for educating health professionals, but no standard approaches exist for training simulation instructors, both for initial training and ongoing professional development. As this education modality continues to expand, there is a need to better understand what interventions and approaches improve the knowledge, skills, abilities and other attributes (KSAOs) for those who are responsible for the design, delivery and evaluation of simulation-based educational sessions.

This scoping review will consider empirical research and other relevant published works that address faculty development for simulation educators in health professions education. This will include faculty development interventions, conceptual and theoretical frameworks, recommendations for implementation and other discussions of issues related to faculty development for SBE. These may include experimental, quasi-experimental, observational, qualitative studies, commentaries and perspectives.

The following electronic databases will be searched: Medline (Ovid); EMBASE (Ovid); CINAHL (EBSCO); ERIC (EBSCO); PsycInfo (Ovid); and Web of Science without time limits. Reference lists of eligible studies will be back-searched, and Google Scholar and Scopus will be used for forward citation tracking. The findings will be summarized in tabular form and a narrative synthesis, to inform recommendations and areas for future research and practice.

Simulation has become a backbone of health professions education. The successes of this experiential learning modality have elicited an ample literature base and its own dedicated peer-reviewed journals (e.g. Simulation in Healthcare; Clinical Simulation in Nursing; Advances in Simulation; International Journal of Healthcare Simulation) as well as academic and professional societies (e.g. Society for Simulation in Healthcare; Society in Europe for Simulation as Applied to Medicine; multiple national simulation societies) and their associated scientific conferences. Further, the growth in simulation has prompted numerous health professions education accreditation bodies to require simulation to be implemented in training programs across the globe [1–12].

With the increasing utilization and importance of simulation-based education (SBE), it is critical that effective, data-driven programs exist to train instructors in SBE. Unfortunately, much of the work that has been conducted on faculty development for SBE is constrained to just one topic: debriefing. While the simulation literature clearly highlights the importance and benefits of debriefing in SBE, and outlines guidance for training instructors how to debrief [13–18], this is just one of many critical competencies required to be a successful simulation educator. Unfortunately, little work has been described in the literature on more comprehensive simulation faculty development initiatives that cover a broader array of critical competencies and their effectiveness.

Understanding what interventions and approaches are currently being used to improve the knowledge, skills and effectiveness of instructors in SBE is an integral step for carving out the future of simulation. Knowing what works, when, for whom and why is critical to be able to map the nomological network of SBE and move the field toward. These data can help inform guidelines, recommendations and potential areas for future practice and scholarship.

We conducted a preliminary search of PROSPERO, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the JBI Evidence Synthesis and identified no current or pending scoping reviews or systematic reviews on the topic. Reviews have been published on particular aspects of simulation faculty development for health professions education, most notably debriefing [19–24]. As well, there are other reviews that cover a particular aspect relevant for simulation educators (e.g. assessment) with no particular focus on simulation faculty development for honing and maintaining these skills [25–28]. Still other reviews report on faculty development approaches in health professions education, but without a particular focus on SBE [29–31]. One review on simulation faculty development has been identified, but this review is almost 10 years old and was focused specifically on high-fidelity patient simulation [32].

Scoping reviews can be used to map the field, elucidate what is known and what remains to be investigated, review the levels of evidence in a particular field, outline methodologies used, be inclusive as to types of work considered and identify knowledge and research gaps [33–35]. This review aims to examine and map the existing methodologies, evidence and constructs pertaining to faculty development for SBE, as well as any reports on the effectiveness of these programs. The scoping review approach, in comparison to a systematic review, will allow us to identify all relevant literature regardless of study design [36].

Our overall question for this review is: What interventions and approaches have been used to date to improve the knowledge, skills, abilities and other characteristics (KSAOs) of faculty in SBE? Additionally, we aim to map the key features of faculty development in SBE, including main content areas, methodologies and approaches used, program leaders and participants, outcomes assessed, demonstrations of transfer of training, and what conceptual and theoretical frameworks are used to inform the design and evaluation of these programs.

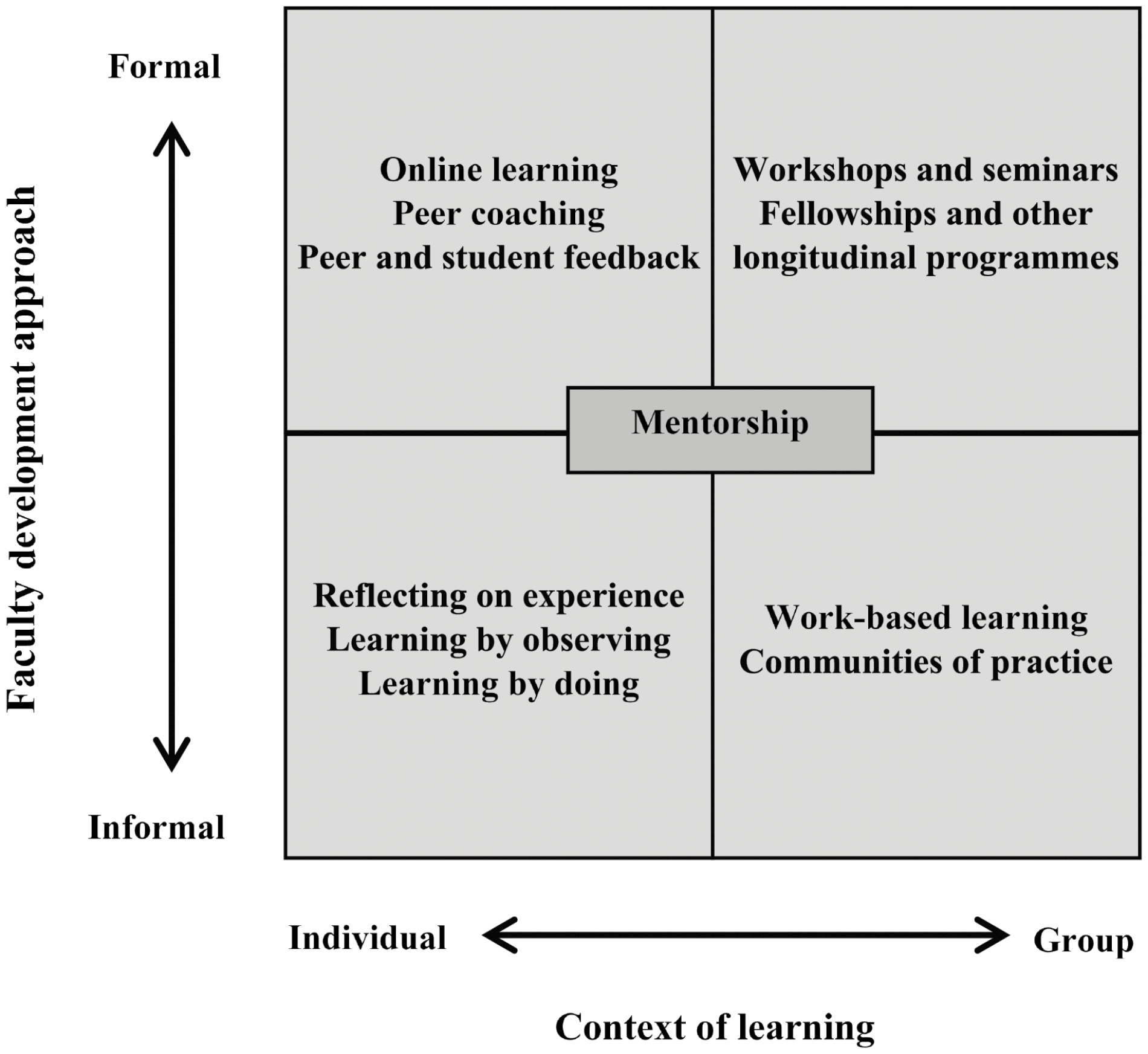

Scoping reviews aim to explore the contours and boundaries of knowledge in an emerging field; as such, the research team felt that a conceptual framework [37,38] would help us to organize our thinking about the task, as well as to help us make sense of the literature we hoped to find. This scoping review will use Steinert’s conceptual framework [39], which situates faculty development activities based on two axes: the approach, from formal to informal; and the context for learning, from individual to group. This model provides an organizing framework from which to explore the faculty development approaches present in the literature, as well as to help identify and articulate gaps in the existing literature base (Figure 1). The model has been widely cited in health professions education, and it also resonates with members of the research group: all faculty development programs identified by members of the research group were able to be situated on the matrix identified by the model.

The organizing conceptual framework for this review is Steinert’s (2010) mapping of faculty development activities, from workshops to communities of practice.

Our review will consider studies spanning all of health professions education. This broad inclusion criteria will ensure key features, methodologies, and outcomes across contexts and learning aims are included.

This scoping review is designed to explore the breadth of faculty development in health professions education. Therefore, all literature that focuses on any aspect of faculty development for SBE will be included. This will not be limited to skills used directly with learners, but will also include any additional knowledge and skills required to be effective simulation instructors (e.g. scenario design, implementation, assessment). Research that focuses on faculty development for health professions educators, but not faculty development specifically for simulation educators (e.g. [30,31]), will not be included.

The context for this review will be international, with no limits. This can include any educational, clinical or geographical setting and studies published in any language.

This scoping review will consider research published in peer-reviewed journals as full manuscripts or conference abstracts, or in the grey literature (e.g. theses & dissertations). All empirical study designs will be considered, including experimental, quasi-experimental, observational and qualitative studies. Systematic reviews and narrative reviews will be excluded but their references will be back-searched.

We will conduct the proposed scoping review in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping reviews [34,35].

The search strategy aims to identify both published and unpublished literature with no predefined timeframe.

The following electronic databases will be searched: Medline (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), ERIC (EBSCO), PsycInfo (Ovid) and Web of Science. An initial limited search of MEDLINE (PubMed) was undertaken to identify articles on the topic. The text words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles, and the index terms used to describe the articles, were used to develop a full search strategy for Medline (Appendix I). A similar search strategy will be customized appropriately for use in each database. Free-text terms will also be included, taking into account synonyms and variants in spelling. The search will not be limited by date or language to maximize the breadth of literature identified.

Reference lists of all included research studies and all relevant reviews will be back-searched, and Google Scholar will be used for forward citation tracking to identify further studies.

All identified citations will be collated and uploaded into EndNote 20.2.1 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and duplicates will be removed automatically and manually. Following deduplication, citations will be transferred to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). A pilot test will be performed by screening 50 titles/abstract jointly by all researchers, for consensus checking of the criteria and their application. Following this, titles and abstracts will be independently screened against the eligibility criteria by three researchers (CC, RD, AR) and by one member of the four-person review panel (AG, DTP, GR, SV). Any discrepancies will be resolved by a third member of the review panel. Following screening, the full text of potentially eligible studies will be retrieved and screened in full to determine eligibility by two reviewers. Any disagreements will be resolved by consensus with the review panel.

Full-text studies that do not meet the inclusion criteria will be excluded and reasons for exclusion will be documented and reported. The results of the search will be reported in full in the final scoping review and presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram.

Data will be extracted from the included papers using an iterative approach, given the anticipated diversity of the identified literature. The data extracted will include citation information; details about the population, concept and context; study methods; and key findings relevant to the review questions. A standardized data extraction instrument will be used in the Covidence system (Appendix II). This has been adapted from the JBI template data extraction instrument for source details, characteristics and results extraction [34], with modifications in relation to the concept of this scoping review. The draft results extraction instrument will be piloted on the first five papers and modified as necessary, and further revisions may be made during the process of extracting data from the remaining studies. Modifications will be detailed in the full scoping review. One review author will extract the data and a second review author will check extraction data. Where insufficient information is provided in the full paper for complete data extraction, the authors will be contacted to provide additional information.

The extracted data will be collated and summarized after descriptive and thematic analyses. The data will be mapped and presented in a diagrammatic or tabular form to assist in answering the research questions. A narrative summary will accompany the results and will describe how the results relate to the review objective and questions. The findings will be discussed as they relate to practice and education. Gaps and limitations of the current literature will also be identified and presented.

We will undertake this scoping review for two primary reasons. Our first goal is to synthesize the existing literature on faculty development for the simulation education community, providing conceptual, theoretical and evidentiary clarity about how to develop and maintain expertise as healthcare simulation educators. Second, and equally important, we aim to identify gaps and areas for future research where a high-quality evidence base is lacking. In this way, we hope that our scoping review will help to define the research agenda for faculty development in simulation education for the coming years.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

| Step | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Faculty, Medical/ | 14,042 |

| 2 | ((medical* or health*) and (teacher* or faculty* or clinician* or educator* or physician* or doctor* or professor* or professional*)).ti,ab,kw. | 555,332 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 563,703 |

| 4 | exp Staff Development/ | 9,712 |

| 5 | ((teacher* or faculty* or clinician* or educator* or physician* or doctor* or professor* or professional* or career*) adj3 (development* or program* or workshop* or growth)).ti,ab,kw. | 36,954 |

| 6 | 4 or 5 | 44,198 |

| 7 | computer simulation/ or augmented reality/ or virtual reality/ | 201,778 |

| 8 | (simulat* or ‘augment* realit*’ or ‘virtual realit*’ or ‘scenario-based*’).ti,ab,kw. | 600,165 |

| 9 | 7 or 8 | 701,940 |

| 10 | 3 and 6 and 9 | 634 |

| Citation details and example characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Citation details | Authors, date, title, journal, volume, issue, pages |

| Country where work was conducted | |

| Study objective or research question | |

| Study design | Interventional study, theoretical, descriptive report, observational study, commentary, review, etc. |

| Type of publication | Full manuscript, abstract, etc. |

| Participant details | Level, specialty, setting, sample size, etc. |

| Details and results extracted from source of evidence (in relation to the concept of the scoping review) | |

| 1. What are the main content areas? | Creating simulations, debriefing for teams, debriefing clinical skills, curriculum design and development, etc. |

| 2. What methodologies and approaches are used in the faculty development activity? | Workshops, virtual/online, self-study, etc. |

| 3. Who is leading or conducting the faculty development activity? | Health professional, educator, peer, etc. |

| 4. What learner outcomes are assessed and evaluated? | |

| 5. Is the intervention/program evaluated? If so, how? | |

| 6. How is transfer of training demonstrated? | |

| 7. What conceptual and theoretical frameworks are being used to inform the design? | |

| 8. If there is an intervention with a control group, what differences emerged? | |

| 9. What is the temporal design of the faculty development program? | One-time session, longitudinal program, short program, etc. |

| 10. Is the program or session in person or remote? | |

| 11. What is the funding arrangement for the faculty development activity? | Funded design, funded for attendees, by whom, etc. |

| 12. What incentives are being used to encourage instructors to attend? | |

| 13. Who is host or organizer of the faculty development activity? | National or international society, hospital, university, etc. |

| 14. Summary of key findings | |