Facilitation of a Massive Haemorrhage Protocol (MHP) is complex, requiring timely co-ordination between hospital teams. Multiple MHP simulations described [1] involve trauma or obstetric patients requiring additional complex actions besides circulatory support. Our experience is that while this is conceptually realistic, there is an inherent distraction from MHP learning when competing trauma-related tasks such as airway protection or chest drains demand participants’ attention during the simulation. This risks cursory rehearsal of MHP, potentially even creating the illusion that MHP has been rehearsed when in fact participants have been focussed on other tasks entirely.

In order to empower teams to rehearse the complex skills required for MHP without distraction we created a simple MHP simulation harnessing principles of cognitive load theory [2].

To minimize the extraneous load of a severe trauma case and the wide array of procedural skills therein we created a simulation in which the team are tasked with administering blood products into a dialysis bag that continuously drains fluid into a second reservoir. Upon commencement the connection between the two bags is opened and the team are advised they cannot stop the ‘bleeding’ and are tasked exclusively with transfusing via MHP to ensure the bag does not empty, while maintaining appropriate protocols and checks utilizing a simulated patient identification sticker and transfusion documentation.

We used expired blood products stored in advance by blood bank to ensure sufficient supply for three paediatric MHP packs which provided physical realism for the tasks involved and bypassed risk of simulated blood contaminating blood bank stock.

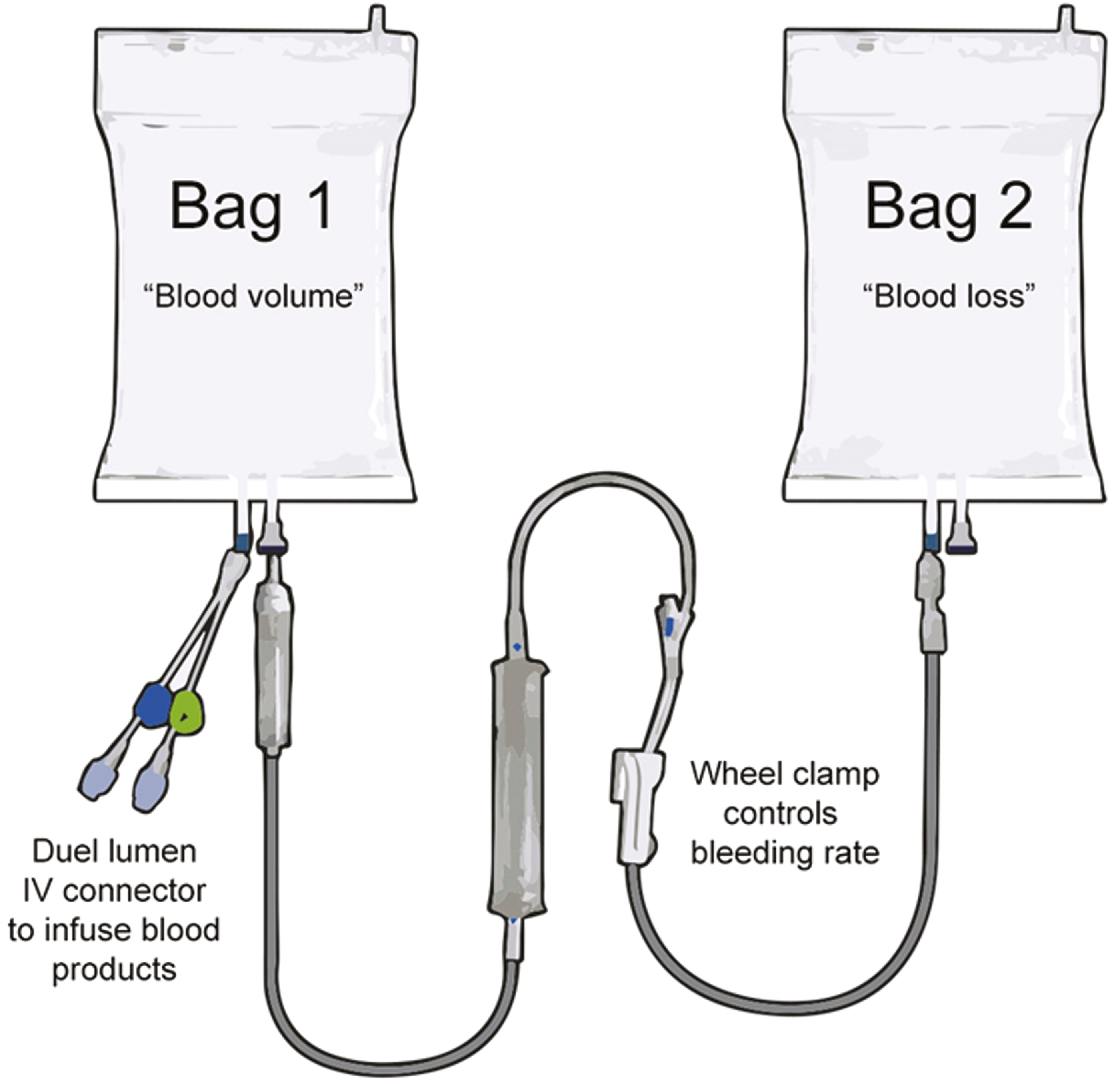

The two chambers were created with two Hemosol 5-L dialysis replacement bags sourced from expired training stock. Each bag includes two access ports. Bag 1, symbolizing the patient’s blood volume had a short, dual-lumen intravenous (IV) line attached to simulate large bore IV access and facilitate infusion of blood products. It was then connected by a second IV line with a wheel clamp to Bag 2, which symbolized patient blood loss [Figure 1].

Simulation assembly guide (items not to scale)

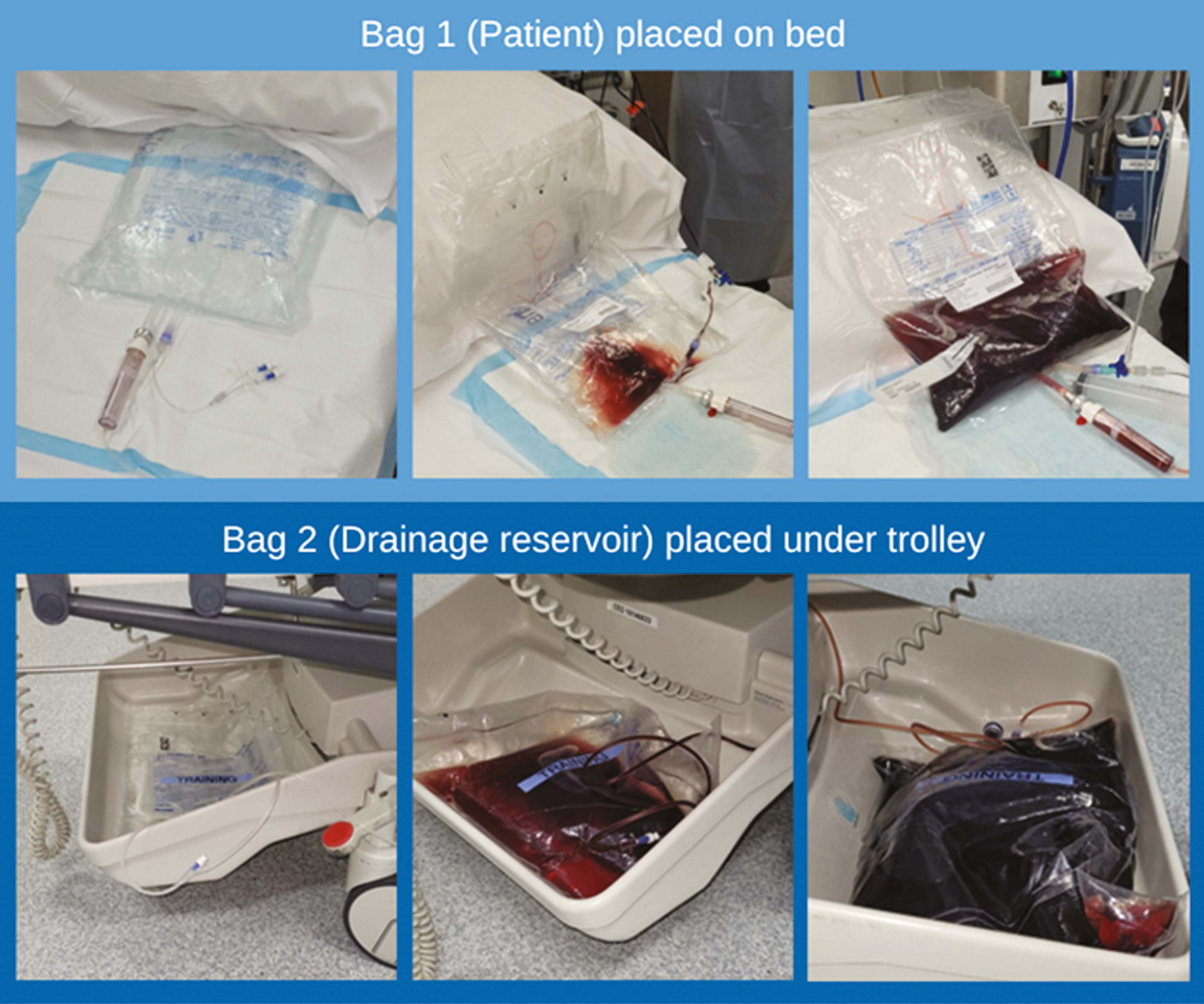

The system was tested to ensure that Bag 1 drained into Bag 2 at a steady rate and could be controlled by the inline wheel clamp to replicate increasing or decreasing blood loss. The maximum flow rate through the IV line was approximately 4 litres per hour. Bag 1 was placed on the bed at an angle to facilitate flow down to Bag 2 underneath [Figure 2]. Both bags were weighed before and after the sim to calculate fluid administration and blood loss.

‘Patient’ and drainage reservoir over course of scenario

The simulation was piloted in a metropolitan paediatric emergency department with a team representing a typical resuscitation team for our service including paediatric emergency registrars, an emergency physician and senior and junior nursing staff. Blood bank staff were online in their department to liaise via phone and also provided multiple observers in the resus room. Analysis of the simulation involved a quality improvement focused debrief, a post-event survey and video review by blood blank.

The blood bank provided a written report identifying multiple recommendations for performance improvement related to education on the rapid transfusion equipment, clarification of the local MHP and potential changes to resuscitation equipment.

Faculty noted that all issues raised in the debrief were related to MHP, implying the scenario kept participants focussed on core learning objectives. The simulation’s simplicity minimized cognitive load on facilitators by excluding the need to run simulation software or provide detailed updates to candidates on the status of the patient. This ensured faculty could focus on documenting the timing of critical tasks such as pack arrivals, time to transfusion of each pack and key phone calls to blood bank while also noting barriers to optimal performance.

A post-simulation survey using Microsoft Forms was sent to participants, observers and faculty with nine responses from 14 involved. The questions were:

1 ‘How likely are you to recommend being involved in an MHP sim?’ (Average score of 9.4 out of 10)

2 ‘How will the simulation influence your future practice?’

3 ‘From your perspective, what process/system factors did the simulation help to highlight? (strengths or weaknesses)?’

The following themes emerged:

Functional Task Alignment: Participants commented on how ‘realistic’ and valuable the simulation felt – our inference is there was high functional task alignment despite low physical realism:

● ‘It was very realistic and a great learning experience....’

● ‘Being able to practice was really beneficial and having the input/out as a visual was great’

Knowledge vs Execution: Participants and faculty commented on the experiential contrast between conceptual knowledge and task execution. They reflected that lecture-based knowledge of the MHP and blood warming equipment protocol was insufficient and valued the opportunity to rehearse the task in depth.

● ‘We… really need to practice these skills and using unfamiliar equipment’

● ‘The manual dexterity required for rapid facilitation of multiple blood products was under-appreciated prior to the simulation’

Protocol, Environmental and Systems Issues Identified: Several staff noted how the simulation aided identification of barriers to efficient transfusion and potential solutions.

● ‘There was a lot of troubleshooting of administration of fluids/blood products such as use of the Ranger warmer, dead space in IV lines, priming IV lines, compatibility of medications and blood products’.

The MHP simulation was simple and inexpensive to create and a powerful visual metaphor. The streamlined pedagogical approach ensured sharp focus on MHP throughout the sim and in the debrief. We encourage teams to consider using this model to rehearse an MHP and will publish the scenario as an open-access simulation [3]. Future revisions may include more accurately representing paediatric blood volume in the dialysis bag sizes.

In addition we advocate consideration of the benefit of similar ‘thin/slice’ simulations when designing scenarios for rehearsal of complex skills, and argue sometimes a less realistic scenario may actually add value to the learning experience.

None declared.

Unfunded project beyond staff salaries.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

1.

2.

3.