COVID-19 has reduced training opportunities for surgical trainees, foundation doctors, and medical students [1]. With elective surgery cancelled, millions of patients on waiting lists, strict requirements on physical distancing, and trainees looking to meet numbers for competencies, it is difficult to achieve the necessary exposure and experience required as per the GMC’s ‘Outcome for Graduates’, the Royal College of Surgeons of England, and the UK medical undergraduate curricula [2,3]. Thus, a hybrid, one day surgical simulation course, aligned to the curricula was designed for attendees to assess, resuscitate, and manage unwell surgical patients.

Candidates were chosen from the region on a first-come, first-serve basis, amongst medical students, foundation doctors, and core surgical trainees. Interactive workshops in the morning were based around theatre etiquette, surgical instruments, suturing, as well as assessing unwell surgical patients. These were followed by high-fidelity surgical scenarios, whereby the candidates were expected to reach a diagnosis, devise an initial management plan, and prepare their patient for theatre. The afternoon consisted of the same candidates carrying out the procedure required for their patient in a theatre setting with senior support available. Medical meat was used for the practical skills component and props, such as a Boyle’s machine were used to simulate the theatre environment. The faculty also played the roles of theatre staff, including an anaesthetist, a scrub-nurse, a floater, and a runner. A high-definition audio-visual system streamed the simulation to the other candidates in the debriefing room. Each scenario was followed by a structured debriefing discussing technical and non-technical objectives, facilitated by surgical consultants. Pre- and post-course questionnaires were completed.

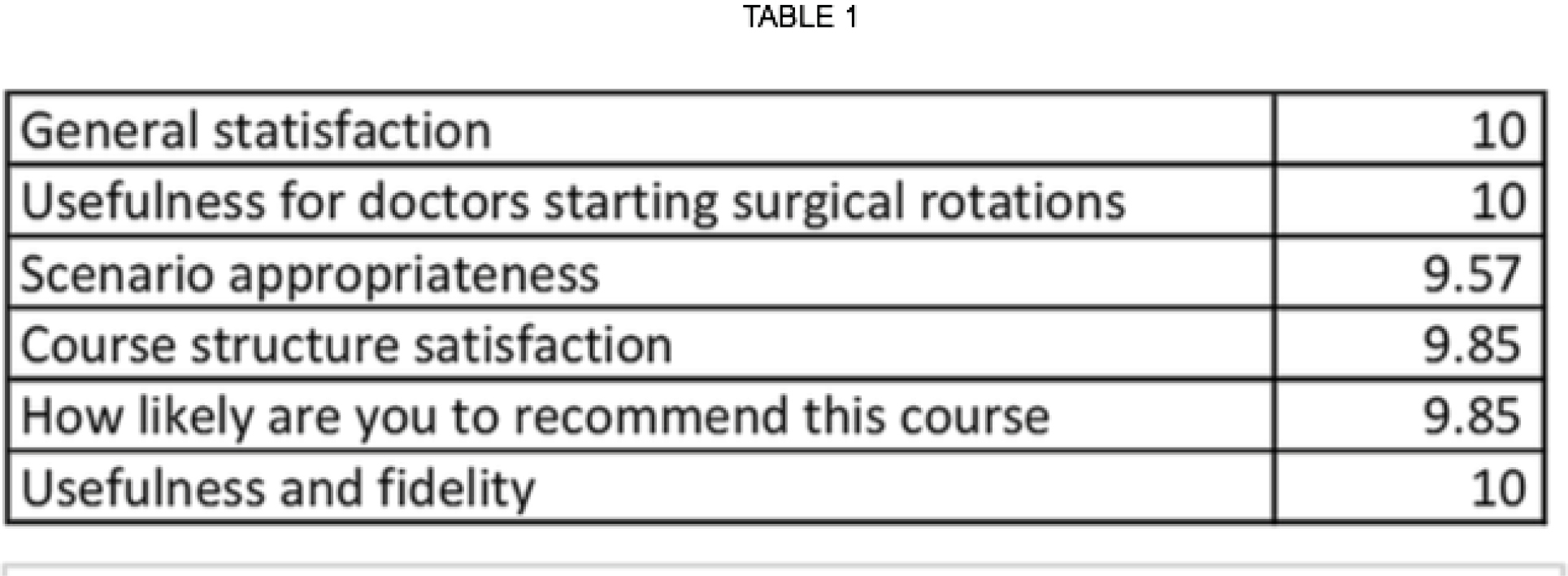

Post-course, all candidates (n=8) provided scores for specific questions. An average of their response for each question, marked out of 10, is presented in Table1.

It is vital to ensure that early exposure to surgical specialities is not disrupted as that is significantly detrimental for tomorrows’ surgeons. Based off evaluation, our course was highly successful in achieving the goals described previously. The variety of candidates at different stages in their surgical career, sharing similar positive opinions about this course further highlights its suitability for all. We endeavour to run more of these courses in the United Kingdom and abroad to ensure that medical undergraduates, as well as surgically inclined junior doctors can develop key surgical competencies and thus are well equipped when caring for surgical patients.

|

1. Munro C, Burke J, Allum W, Mortensen N. COVID-19 leaves surgical training in crisis. BMJ 2021;n372.

2. Carr A, Smith J, Camaradou J, Prieto-Alhambra D. Growing backlog of planned surgery due to COVID-19. BMJ. 2021;372:n339.

3. General Medical Council. Practical skills and procedures. 2019. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/practical-skills-and-procedures-a4_pdf-78058950.pdf?la=en&hash=9585CB5CA3DA386B768F70DAD3F62170C2E987E5 [Accessed on 18/07/2022]