Emergency departments can often be the first place to which people present when in mental health emergencies, although these departments and staff are not always adequately supported to meet the needs of these patients. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of simulation-based training for mental health crisis in the emergency department on knowledge, confidence and attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration.

Healthcare professionals (n = 85) from a range of professions participated in a multicentred simulation-based training activity. Questionnaires evaluating participant knowledge, confidence and interprofessional attitudes were administered pre- and post-activity, and analyses were conducted. Thematic analysis was conducted on free-form participation simulation training evaluation forms.

Participants reported that the simulation training improved their communication skills, clinical practice, encouraged reflective practice and promoted interprofessional collaboration between emergency department and mental health professionals. Significant improvements were seen in participant knowledge and confidence in providing care to individuals presenting to emergency departments in mental health crises. Attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration in a variety of domains improved because of taking the simulation training.

The pedagogical qualities of the in-situ simulation-based training presented fostered interprofessional collaboration and allowed participants to achieve challenging outcomes. It is suggested that further research should investigate the impact of simulation-based training on mental health related patient care outcomes in the emergency department.

Media coverage has brought to public attention examples of poor care being administered by emergency departments (EDs) to individuals presenting in mental health (MH) crises [1]. Instances of MH emergencies in EDs appear to be increasing in prevalence, whilst the availability of specialist MH care is limited [2]. Due to a lack of MH education, ED staff often implement restrictive intervention in mental healthcare settings [3]. For example, patients in MH crisis are often met with restraints and/or seclusion by ED staff, which is posited to induce adverse psychological outcomes for those affected [3]. Critically, ED professionals lack knowledge and confidence in caring for and assessing patients experiencing MH crises, which can have an adverse impact on patient care [4]. The availability of psychiatric liaison services in the UK is growing, while ED professionals exhibit a desire to receive training [5]. Offering MH educational interventions to ED professionals may be more beneficial, yet few validated educational programmes exist. The lack of evidence on validated training programs addressing MH crises in the ED is a critical gap in the literature, which this study seeks to address.

Prior literature has established that providing training to EDs improves patient outcomes. One study [6] found that providing ED professionals with an evidence-based educational intervention on human trafficking improved participants’ confidence in identification and treatment of human trafficking victims in the ED. Further, one mixed method pilot study [3] found that providing a trauma informed care (TIC) educational intervention to ED nurses improved participants’ knowledge and confidence in providing TIC to individuals presenting to ED in MH crises, and enhanced person-centred care. Additionally, an integrative [7] review found that providing multidisciplinary simulation-based resuscitation team training to ED trauma teams had the potential to improve communication, leadership and interprofessional collaboration, holding implications for improving patient outcomes. Thus, empirical evidence supports the notion that providing ED professionals with educational interventions can be beneficial, with improvements being seen in participants’ confidence, knowledge and provision of care.

Simulation-based training (SBT) is increasingly being utilized as an educational intervention within mental healthcare [8]. In this approach, based on experiential learning models, participants engage with simulated patients, allowing them to develop and practice skills in a realistic but controlled environment. Its benefits have been well described [9], not least its ability to facilitate active participation and attitudinal change, SBT is particularly suited to improving efficacy in technical skills, increasing knowledge and confidence, and improving behavioural skills such as communication and interprofessional collaboration [9, 10–12]. Interprofessional collaboration refers to the process in which different professional groups work together collaboratively to positively impact healthcare outcomes [13]. It involves the interaction and negotiation between professional with different expertise and contributions [13] and is vital to ensuring successful healthcare provision [14]. Based on previous research [15], SBT emphasizing interprofessional collaboration between MH and ED professionals may support management of MH emergencies in EDs. However, the role of attitudinal change in promoting interprofessional collaboration in in-situ simulation training is unclear. As in-situ SBT is a team-based training method which brings learning into closer proximity with the workplace and working conditions of clinicians, its increased realism is posited to strengthen communication and collaboration between healthcare workers [16] and may hold implications for influencing attitudinal change. This pilot study reports a novel multicentre in-situ SBT programme for ED and MH professionals, and aims to assess the impact of SBT on participants’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration [8, 12].

This study employed a mixed-methods pre-post evaluation design using de novo and validated survey measures. A multicentre in-situ SBT aimed to improve participant confidence, knowledge and attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration. Ethical approval was obtained from the Psychiatry Nursing and Midwifery (PNM) Research Subcommittee at King’s College London and informed consent was obtained before participation.

At each hospital site emergency department nurses, psychiatry liaison nurses, drug and alcohol specialist nurses, emergency medicine trainee doctors, liaison psychiatrists and security personnel were invited to sign up to take part in the simulation training. The simulation activity was delivered to 85 attendees over 12 occasions (average class size included 7 participants) who were recruited using opportunity sampling and consented prior to the training. The professions of the attendees included ED nurse (n = 21), ED doctor (n = 17), psychiatric liaison nurse (n = 23), psychiatric trainee (n = 5), security (n = 12), and other (n = 7). Participants completed pre-post training surveys which collected limited demographic data.

The SBT was delivered in EDs across London and Southeast England, using clinical areas for both simulated scenarios and reflective debriefs. A short didactic session which provided an introduction to simulation training, in addition to outlining the ground rules and aims of the simulation activity, followed introductory steps to ensure psychological safety. Three different simulation scenarios were offered: (1) triage, (2) assessment and (3) treatment, which required participants to engage with a simulated patient in MH crises. The three-part evolving scenario followed the simulated patient’s journey from triage through to majors and was designed to draw out learning points around assessing risk, mental capacity and the interface between mental and physical health. The simulated patient was presented with character background information, as well as instructions for each scenario. Please see appendices A, B and C for scenario scripts. The simulation activity was based on Kolb’s experiential learning cycle [17] and delivered by an interprofessional team, including an Emergency Medicine consultant, a Liaison Psychiatry consultant and two trained faculty facilitators who were MH nurses or psychiatric trainees. The simulated patient was a middle-aged male living with chronic schizophrenia, poorly controlled type II diabetes, which had resulted in a necrotic foot ulcer, and co-morbid alcohol misuse, who self-presented to the ED in a confused and agitated state. Each simulated scenario was conducted as a group and required active involvement from a minimum of two interprofessional participants, lasting for 15–20 minutes. The first participant was instructed to speak to the simulated patient, before seeking help from a second participant – who was from another profession and had not seen the first participant’s actions. The remaining attendees observed the scenario, via video-link, in another room. Following each simulation scenario, all participants were debriefed by 2 trained facilitators using the Diamond method [18] , lasting 45 minutes. Please see Appendix D for a diagram depicting the Diamond Debrief Model [18] . The debrief session was designed to elicit learning around behavioural/human factors as well as allowing for clinical questions to be addressed. Particular efforts were made to create an emotionally safe learning environment in order to assist participants to learn positively and constructively from the experience. Scripts and videos were not used during the debriefs. For a detailed description of the simulation training learning objectives, timetable and scenarios, see Table 1.

| Course learning objectives |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Time | Title | Learning activity |

| 08.15–08.30 | Welcome | Registration, filling in consent forms and pre-course assessment |

| 08.30–09.00 | Introduction | Ice-breaker games. A PowerPoint presentation detailed what simulation training is, what the ground rules of the course were, and the aims and objectives of the course. |

| 09.00–09.15 | Scenario 1 | Introduction to ED patient. History of schizophrenia, uncontrolled diabetes and comorbid alcohol misuse. The task is to perform a brief assessment in order to triage the patient and make a brief risk management plan. |

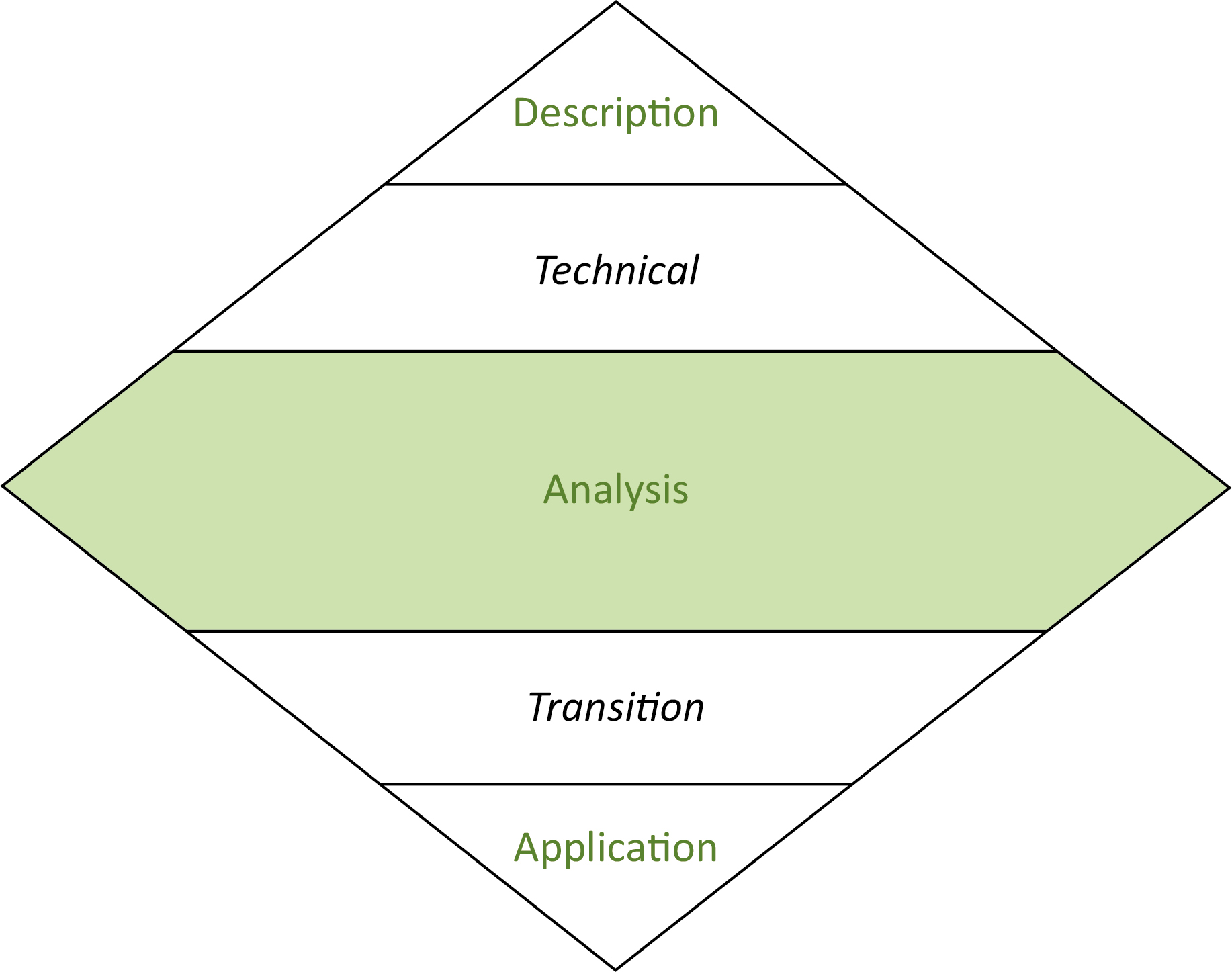

| 09.15–10.00 | Debrief 1 | Participants asked to write down risk factors and risk management plan, in the format Description, Technical Skills, Analysis, Application. |

| 10.00–10.15 | Scenario 2 | Participant is instructed to carry out a medical assessment including vital signs, obtaining a BM, and, if appropriate, taking blood samples. Confer with professional from another team. |

| 10.15–11.00 | Debrief 2 | Discussion around the capacity of the patient in the format Description, Technical Skills, Analysis, Application. |

| 11.00–11.15 | Break | |

| 11.15–11.30 | Scenario 3 | Participant is instructed to start treatment – intravenous fluids and antibiotics. Additional observations required. Negotiate plan with patient. |

| 11.30–12.00 | Debrief 3 | Actor is encouraged to reflect on participants’ actions. This may cover, assessment of capacity, legal framework, restraint, rapid tranquilization in the format Description, Feedback from Actor, Technical Skills, Analysis, Application |

| 12.00–12.15 | Summary | Wrap up of the course and closing. |

| 12.15–12.30 | Break | |

| 12.30–13.00 | Post-course evaluation | Participants were required to fill out post-course evaluation forms comprised of free-text questions (for example, how useful do you think sessions like these will be for your work with patient/client group?). |

| 13.00 | End | |

Note. The cited information (Table 1 scenarios) is not from an actual patient. Any resemblance to a real person living or deceased will be coincidental.

Two pre- and post-activity self-report measures, a Confidence & Knowledge measure and TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire (T-TAQ) [19], were administered to all participants.

The 22-item Confidence and Knowledge measure contained two parts and was created de novo for this study; part A used true/false questions to assess knowledge regarding key concepts covered during the simulation training on conducting a mental capacity assessment, and part B required participants to rate their confidence on a 0–100 Likert scale (0 = ‘cannot do at all’, 100 = ‘highly certain can do’) regarding the use of legal frameworks, patient interaction, confidence regarding risk assessment skills and interprofessional collaboration. The confidence and knowledge measures were created de novo for this study so to increase concordance between the simulation training content and the item content, as previously validated scales were not fully applicable to the scope of the study. Please see Appendix E for the list of items included.

The reliable and validated T-TAQ assessed changes in participants’ interprofessional collaboration attitudes, looking specifically at Team Structure, Leadership, Situation Monitoring, Mutual Support and Communication. The T-TAQ consists of 30 questions (6 per dimension) and requires participants to rate their level of agreement on a 5-point scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. Prior research [20] utilized Cronbach alpha statistics to assess the T-TAQ’s reliability, and acceptable internal consistency was found in all domains, team structure (α = 0.70), leadership (α = 0.81), situation monitoring (α = 0.83), mutual support (α = 0.70) and communication (α = 0.74). Construct intercorrelation coefficients ranged from 0.36 to 0.63 [20], indicating that, although the constructs overlap to some degree, the T-TAQ possesses discriminant validity.

A self-report simulation activity evaluation questionnaire, consisting of 12 items, was administered to all participants post-SBT. It was comprised of free-text questions which aimed to capture the attendees’ experiences and opinions regarding the impact of the simulation training. Please see Appendix F for a list of all items included in the self-report evaluation form.

Paired-sample t-tests using IBM SPSS statistics 24 explored changes in participant confidence, knowledge and attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration pre- and post-all simulation activities. Braun & Clarke’s (2006) validated method of thematic analysis [21] was used to explore the qualitative data. Responses from the course evaluation forms were compiled into an Excel document which detailed the respondent number, the date of the course, the ratings and the comments for each open-ended question. Two of the study authors read through the simulation activity comments multiple times and generated initial codes independently. Emerging themes were identified collaboratively by the authors, then reviewed to ensure they captured all of the initial codes. Final themes were defined and named collaboratively and described by the lead author.

The half-day SBT was run by Maudsley Simulation and Learning on 12 occasions across 9 hospital sites in Southeast England between May 2016–May 2017. One commissioned simulation activity was cancelled due to a lack of interest – only 5/12 spaces were filled. The simulation training had a fill rate of 78% (112/144 spaces filled) and an attendance rate of 76% (85/112 attended).

Paired-sample t-tests found that participants’ mean confidence and knowledge scores improved statistically significantly from pre- to post-activity. Progressive improvements in participants’ confidence (t(75) = 9.289, p <.001) and knowledge (t(75) = 6.927, p <.001) were found as the learning journey progressed.

Paired-sample t-tests were used to analyse the T-TAQ data and statistically significant improvements were found in all domains, team structure (t(64) = 5.94, p <.001), leadership (t(64) = 2.48, p = .016), situation monitoring (t(64) = 5.41, p <.001), mutual support (t(64) = 2.81, p = .007), and communication (t(64) = 3.47, p = .001). Participants’ attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration, (t(64) = 5.981, p <.001), improved as the learning journey progressed when comparing mean pre- and post-activity scores. For a detailed description of the confidence, knowledge and T-TAQ inferential statistics, please see Appendix G.

Qualitative data explored participants’ views and experiences of the simulation activity. Thematic analysis [21] of the free-text activity evaluation forms revealed four themes: (1) interprofessional collaboration, (2) communication, (3) knowledge and patient care and (4) reflective practice. Participants most regularly highlighted that the simulation activity benefited their interprofessional collaboration and was representative of what multidisciplinary teams are expected to deliver.

Respondent 2; R2: It was really helpful and a great opportunity to work with colleagues from the ED away from a clinical setting.

Further, they reported improvements in their understanding of procedures, pressures and limitations their professional counterparts face which they believed would facilitate increased interprofessional collaboration and a better working environment in the future.

R7: [I learnt that] that the ED need support from mental health professionals to manage a patient for their best interest.

R1: Integrating people from different specialities and putting them together in a simulated environment [aids] learn[ing about] the strengths and weaknesses of these specialities and encourages people to get advice from these specialities in the future.

Respondents noted that the simulation activity ‘reinforced that communication is important’ (R29), especially when employing ‘de-escalation tactics’ (R14) with patients experiencing MH crises and when conversing with colleagues of different professions.

R8: [It is important to] discuss with colleagues in A+E.

R14: [The simulation activity] helped me to reassess that there may not be an ‘expert’ who know it all, so sharing ideas is important to make a collaborative decision.

Improved knowledge regarding procedure, protocols, mental health conditions and the pathways of one’s own and others’ professions, was commonly reported. Specifically, participants reported an improved awareness and appreciation of the role played by other professions when managing a mental health crisis. Participants also noted improved knowledge of applying the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) and Mental Health Act (MHA), which was further reiterated by improvements in the knowledge scale. Ultimately, through improving their knowledge on interprofessional collaboration and the relevant clinical and legal protocols, participants reported improved understanding of caring for individuals during a MH crisis.

R6: [I learnt about] the role of the ED doctors and their knowledge of mental health.

R17: [The activity improved my] understanding the legalities of MCA/MHA.

R30: I [now] understand how to care for [individuals experiencing MH issues in the ED].

Respondents also indicated that the simulation activity gave them the opportunity to reflect thus enabling them to empathize more, modify their attitudes, and have more patience with individuals experiencing MH crises.

R10: [I found it useful to] focus on reflecting back to patient to confirm / clarify.

R17: [The activity] increased my compassion and tolerance of duration of symptoms.

R:19: [The activity helped me to become] more reflective of approaches and how things can be approached in different ways.

The findings suggest that SBT is well received by both MH and ED employees, with participants reporting that the simulation activity benefited their interprofessional collaboration, communication skills and provision of care and encouraged reflective practice. Currently, the provision of care to those presenting to ED departments in MH crises is poor. A lack of confidence and knowledge on the part of ED professionals is posited to result in poor provision of care. SBT training programs have been found to promote interprofessional collaboration [15] and facilitate active learning [9]. The present study replicates these findings. It was found that the simulation activity promoted interprofessional collaboration between ED and MH professionals. Further, the simulation activity improved other human factor skills which are vital for all aspects of clinical work, including effective communication and reflection. Thirdly, the findings suggest that simulation training attendance led to statistically significant improvements in participant confidence, knowledge and attitudes towards individuals in MH crises presenting to EDs. Notably, participants highlighted improvements in their knowledge of medical and legal protocols to conduct mental capacity assessments, and improvements in their confidence to collaborate with other professionals. Furthermore, the ability of the training intervention to improve attitudes measured with a validated tool may demonstrate the pedagogical qualities of SBT to achieve challenging learning outcomes, relating to the interactive use of simulated patients and reflective learning. These findings may also be influenced by the in-situ delivery of the training in EDs, bringing learning into closer proximity with the workplace and working conditions of clinicians.

This study extends from the literature by creating a multicentred SBT activity for ED and MH professionals aiming to improve responses to MH emergencies in the ED. Improving interprofessional collaboration is particularly important in this context as often professionals are required to function collectively in multidisciplinary teams at short notice so to achieve high quality, safe care [11]. Further, the importance of improving human factor skills is particularly relevant in an emergency setting, where effective communication is necessary to provide complex patient management under pressure [11]. Critically, the innovative multicentred nature of the SBT training presented could enable standardization of MH care in the ED across several institutions.

The results of this study should be considered in the context of its limitations. Firstly, recruitment presented a challenge, with one simulation training activity being cancelled due to lack of interest. Findings suggest that ED and MH professionals are keen to receive SBT, and that participant outcomes benefit from greater attendance. Yet, structural issues such as workload and staffing pressures, low availability of cover and orchestration across different trusts limited attendance. This could introduce bias into our findings as professionals from lower-resourced institutions were less likely to attend the simulation training. Limited demographical information was collected, thus comparisons between different institutions were not possible. Further, the reporting of demographical information is salient when determining the generalizability of result findings. Factors such as age, gender or ethnicity can influence the extent to which the simulation activity improved participants’ confidence, knowledge and interprofessional collaboration. Thus, lack of adequate demographical information is a methodological weakness of this study. Another limitation is that the confidence and knowledge measure used had not been previously validated; the measures were created de novo for this study so to increase concordance between the SBT content and the item content. Specifically, the knowledge measure comprised of true/false questions may not be fully reflective of learning, as participants completed this unsupervised, and the results may contain an element of guessing. Future studies should consider alternative measures of knowledge, such as observation-based assessments or interviews to provide more robust data. Further, the confidence measure utilized a 1–100 scale, as opposed to the traditional 1–5 Likert scale. This scale was chosen as including a larger range of possible answers has the potential to better reveal the participants’ perspective and broaden the scope of understanding. However, this study acknowledges that often participants may view the 1–100 scale as arbitrary, leading to inaccuracy. Third, this study utilized self-report data. Due to resource constraints, self-report free-text evaluation forms were used. However, utilizing self-report free-text evaluation forms, compared to structured qualitative interviews, limited the depth and richness of the data produced. Most comments given were short in length and did not richly describe the views and experiences gained from completing the simulation activity. This limited the quality of the thematic analysis, as the lack of rich data prevented the generation of an in-depth understanding of the impact of the simulation activity on participants. Comparatively, qualitative interviews would allow for a richer understanding gleaned from personal interaction. They would also allow researchers to probe further when respondents give short or shallow comments. Fourth, based on participant feedback, it is advised that subsequent SBT activities include more scenarios and longer teaching time within-scenario. Lastly, the current study did not examine behaviour change in practice, therefore was unable to evaluate whether improvements in interprofessional collaboration were sustained when managing complex patient needs under pressure in the ED.

This pilot study holds multiple implications for wider SBT research, with study findings providing a basis for future research with a range of considerations. This study used a de novo confidence and knowledge measure as previous validated measures were not relevant enough to activity content. More specialized tools need to be developed and validated to measure learning and confidence in response to MH emergencies in the ED. Further, this study highlights how structural issues limit engagement with the target population. Future training should be delivered in partnership with the ED departments to increase engagement, resulting in increased attendance and sample size, which has the potential to benefit participant outcomes and the reliability of statistical findings. Additionally, methods such as in-depth qualitative structured interviews should be employed to understand the mechanisms driving change in the training. Studies that utilize longitudinal follow up procedures may shed further light on these mechanisms. Lastly, future research could seek to evaluate if the multicentred SBT training had impact on subsequent provision of care in the ED.

The presented SBT activity has the potential to improve outcomes in the ED through educating ED professionals on MH issues and promoting interprofessional collaboration. The pedagogical qualities of in-situ SBT allow participants to achieve challenging outcomes and learn in an environment which mirrors the workplace. Further, through educating ED professionals on MH emergencies, interprofessional SBT programs have the potential to reduce the level of burnout in MH and ED professionals. The successful implementation of a multicentred, interprofessional SBT program could improve the care of patients in MH crises presenting to EDs across numerous institutions.

Maya Ogonah and Marta Ortega Vega led on drafting the manuscript, while all other authors contributed to the overall project.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery (PNM) Research Ethics Subcommittee at King’s College London (ref. no. PNM/13/14–173) and informed consent was obtained before participation.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

| Basic scenario (15 min) | This scenario is divided into 2 parts and takes place in 2 adjacent environments: triage room and PLN office (where a private discussion can take place). The Mr O’Neil remains in the triage room throughout. Props: Obs equipment, telephone, Cas Card |

|

|---|---|---|

|

ED nurse 1 | Mr O’Neil has self-presented to ED. The ED nurse’s task is to perform a brief assessment in order to triage the patient and make a brief risk management plan. |

|

PLN 1/Psych trainee 1 and ED nurse | The ED nurse has been primed that she may wish to consult with a PLN/Psychiatry trainee in the PLN office. Together, they should discuss any available risk history and make an immediate risk management plan. The PLN/Psychiatry trainee had already been provided with a print-out of the patient’s electronic records. |

|

All participants | The ED nurse +/- the PLN/Psych trainee return to triage to explain the initial management plan to Mr O’Neil. |

| Instructions to participant | ||

| ED nurse 1 | You are assessing Mr O’Neil in triage. He has self-presented to ED. As part of your initial assessment, you will need to conduct a brief risk assessment. You may wish to discuss with the PLN/Psychiatry trainee who are available in the PLN office next door in order to make an initial management plan. You will need to communicate this plan to Mr O’Neil. | |

| PLN 1/Psychiatry trainee 1 | You may be asked by the ED nurse to look Mr O’Neil up on the electronic records and provide some background information. Together with the ED nurse, you are tasked with making an initial management plan to contain any immediate risks. The ED nurse may want you to join him/her to communicate this plan to Mr O’Neil. | |

| Instructions to actor | ||

| Background information You are a 55-year-old gentleman with a background of chronic paranoid schizophrenia, alcohol problems and chronic physical health problems (type II diabetes, high blood pressure, chronic foot ulcer). You live in supported accommodation (Framingham House) with 5 other clients (Harry, Prince, Faizer, Leroy and Terry). You are currently under the Community Rehabilitation Team. You can’t remember the name of your community team, but remember that your care coordinator is called Joy and your key worker is called Derek. You refer to them in disparaging terms. |

||

| You were born and raised in Chatham. You are a lifelong Gillingham FC fan. You moved to Surrey (for a girl) 30 years ago. You were rehoused to supported accommodation Chertsey 5 months ago. You have never held a long-term job due to periods in hospital or street homelessness since your youth. You had worked as an ‘odd job man’ for short periods in your 20s. Both of your parents have passed away. You believe your father was an alcoholic. You have 5 older siblings, but are only in occasional phone contact with your sister, Shelagh, who lives in Dover. You are not currently in a relationship. You have a daughter (Maeve) who’s in her mid-20s. You have not had any contact with her for 20 years. You are working class, and talk with a Kent (or vaguely estuarine) accent. Feel free to be liberal with expletives and colloquialisms. | ||

| In recent weeks, you have been increasingly erratic with compliance with your physical health and mental health medications. You can’t remember what you are on, but recall that you have blood pressure problems and diabetes. You are fed up of having injections for your diabetes. You have a nasty foot ulcer, and walk with a limp (you have an ulcer on the ball of your right foot). You become angry if this is mentioned: ‘it’s nothing’. | ||

| Instructions for scenario You have come to A&E because you want to be moved into a new flat. You are having difficulties in your accommodation. You repeatedly state that you ‘can’t go back’ to your flat. You are ‘sick to death’ of your fellow residents, who you feel have been ‘snooping through’ your belongings. You had a big argument with a resident last night, who you are convinced has stolen your money. You are very fixated on what you think that your fellow residents have done. You resist being moved away from this topic area. |

||

| You appear dishevelled and have a soiled bandage around your right foot. If anyone comments on it, you dismiss their concern. Do not allow the candidate to examine your foot. You behave as if you are intoxicated. Your speech is slightly slurred and, at times, incoherent. You become angry if anyone brings up alcohol. You are perplexed but a little irritable. You mutter to yourself and appear suspicious, looking round the department. Your speech is slightly muddled and you are disorientated in time and place (sometimes thinking that you are in Chatham). You are highly distractible. You are paranoid about being under surveillance by the police. If this is enquired about in a sensitive manner, you reveal that you are convinced that you have been accused of being a member of the real IRA and have been monitored by the Met anti-terrorism squad for 30+ years. You are guarded, and may accuse participants that their conversation is being recorded. | ||

| You do not have any thoughts of harming yourself. You have often thought about confronting your fellow residents about your suspicions that they are going through your things. You did, in fact, confront Faizer (who lives in the neighbouring room) last night, whom you also believe is part of IS (Islamic State), which led to an argument. You are very guarded if asked about possession of weapons. In Part C of the scenario (when the participant returns to explain the plan to you), you might reveal that have a knife hidden in your room (for self-defence), but won’t reveal where. | ||

|

||

| Basic scenario (20 min) |

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

PLN 2/Psych trainee 1 | The participant has been asked to join the ED nurse to commence a mental health assessment. |

|

Senior ED doctor 1 | The participants (apart from the security officer) may wish to discuss the patient with an ED doctor in the PLN office. If this does not take place after 10 minutes, the ED doctor will be asked to check on the participants in majors, and ask if they need support. |

| Instructions to participant | ||

| ED nurse 2 |

|

|

| PLN 2/Psych trainee 1 |

|

|

| Security officer 1 | Following the initial risk assessment, you have been asked to provide ‘within eyesight’ level of observation of Mr O’Neil. | |

| Senior ED doctor 1 | You have been busy in majors managing other patients, but are available should the team wish to discuss Mr O’Neil with you. | |

| Instructions to actor | ||

| You are fed up of waiting around. You feel that nothing is being done about your accommodation. You want to leave. You have no plans about where you are going to go, but are prepared to sleep on the streets: ‘I slept rough for 10 years’. You don’t feel safe in the department, and are becoming concerned that people are watching you and might be providing the police and MI5 with information about your whereabouts. | ||

| You don’t see what checking your blood pressure and taking blood tests has anything to do with sorting out somewhere for you to live. You’ve ‘wasted enough time’ in the department and have ‘important things to do’. ‘You’re f***ing’ useless’ anyway, as no one has bothered sorting out alternative accommodation for you. | ||

| If asked, you state that you have not had any insulin for about a week. You have been suspicious that the district nurses are involved with the police. You don’t believe that you have diabetes anyway; you think it may have been some kind of elaborate ruse to keep you ‘drugged up’. You are vague about when you last took Risperidone. You don’t need it; ‘never have needed it; just take it to keep them off my back’. You do not have any | ||

|

||

| Basic scenario (15 min) | This scenario is divided into 2 parts and takes place the same environment: a cubicle in majors. | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Senior psych trainee 2/Senior ED doctor 1 | The participants (apart from the security officer) may wish to discuss the patient with a senior doctor in the PLN office. If this does not take place after 5 minutes, the senior doctor will be asked to check on the participants in majors, and ask if they need support. |

|

All participants | The participants will return to majors to negotiate a plan with the patient. |

| Instructions to participant | ||

| ED nurse 1 | You are looking after Mr O’Neil in majors and have just come on shift. You would like to perform another set of observations. | |

| Junior ED doctor 2/Psych trainee 1 | You have just taken over from your colleague and have been asked to explain to Mr O’Neil the management plan. | |

| Security officer 2 | You have taken over from your colleague in providing ‘within eyesight’ observation of Mr O’Neil. You have not received any instructions as to whether or not it is appropriate or not to restrain Mr O’Neil if he is attempting to leave. | |

| Senior psych trainee 2/Senior ED doctor 1 | You are available to provide senior support to trainees in the department. You do not have immediate access to patient records, therefore are reliant on presented information in order to make a decision. | |

| Instructions to actor | ||

|

||

Please answer the following True/False statements:

| Statement | True | False | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Only mental health practitioners should assess patient’s decision-making capacity. | |||

| 2 | A central principle of the Mental Capacity Act is to assume capacity. | |||

| 3 | Section 5(2) cannot be used to hold patients in the Emergency Department against their wishes. | |||

| 4 | Patients presenting with a mental disorder always lack capacity with regards to treatment decisions. | |||

| 5 | The best predictor of future risk events is past behaviour. | |||

| 6 | Current mental state is an example of a static risk factor. | |||

| 7 | Risk to self includes risk of self-neglect. | |||

| 8 | A risk management plan should include steps to modify dynamic risk factors. | |||

| 9 | Altered and fluctuating level of consciousness is a common feature of schizophrenia. | |||

| 10 | Psychiatric assessment should not take place until the patient’s physical health assessment and management plan is complete. |

Rate your degree of confidence for each item below by writing any number between 0 and 100, using this scale:

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Cannot do at all Moderately certain Highly certain can do Can do

| Confidence (0–100) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify when I need for perform an assessment of a patient’s decision-making capacity. | |

| 2 | Initiate an assessment of a patient’s decision-making capacity. | |

| 3 | Perform a brief risk assessment. | |

| 4 | Ask for necessary assistance from colleagues. | |

| 5 | Ask for necessary information from colleagues. | |

| 6 | Make a risk management plan. | |

| 7 | Communicate useful information effectively with colleagues. | |

| 8 | Work with colleagues to effectively manage an agitated patient. | |

| 9 | Understand the legal frameworks that can be used when managing patients who refuse treatment. | |

| 10 | Take a leadership role in an emergency clinical care situation. | |

| 11 | Work as part of a team to manage a challenging clinical situation. | |

| 12 | Provide compassionate care to all my patients. |

| What is your current NHS role? | Physician □ | Registered General Nurse □ | Registered Mental Health Nurse □ |

| Psychiatrist □ |

|

|

Please complete this form as fully as possible to help us plan future courses (use the back of the page if required). Please rate each question out of 5 (using the scale below) and write any comments you wish to make.

| Inadequate | Poor | Satisfactory | Good | Very Good | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1 |

|

Comments: | |||

| 2 |

|

Comments: | |||

| 3 | How would you rate the facilitator(s) on this course on the following: | ||||

| a) |

|

Comments: | |||

| b) |

|

Comments: | |||

| c) |

|

Comments: | |||

| d) |

|

Comments: | |||

| 4 |

|

Comments: | |||

| 5 |

|

Comments: | |||

| 6 | List 1 thing (or more) you found useful about the course. | Comments: | |||

| 7 | List 1 thing (or more) that could be improved. | Comments: | |||

| 8 |

|

|

|||

| 9 |

|

Comments: Please state in what way. | |||

| 10 |

|

Comments: Please state why you would either recommend or not. | |||

| 11 | How did you hear about this course? | Comments: | |||

| 12 |

|

Comments: | |||

| Mean (SD) | SE | df | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | −1.24 (1.56) | .179 | 75 | −6.927 | .000* |

| Confidence | −155.90 (146.31) | 16.783 | 75 | −9.289 | .000* |

| Structure | −1.79 (2.42) | .300 | 64 | −5.944 | .000* |

| Leadership | −.79 (2.55) | .317 | 64 | −2.478 | .016* |

| Situation monitoring | −1.65 (2.45) | .304 | 64 | −5.412 | .007* |

| Mutual support | −1.01 (3.09) | .384 | 64 | −2.806 | .001* |

| Communication | −1.01 (2.50) | .310 | 64 | −3.470 | .000* |

Note. * p < .001.